Palestinian Photography 1891-1948 (2000, translated from Hebrew)

Palestinian Photography 1891-1948 (translated from Hebrew, 2000, at academia website) | | | | Abstract | | |

The exhibition and the book characterize and chart the major lines in Jewish (institutional and independent) and Palestinian photographic activity in Palestine during the 1930s and 1940s. During these years Jewish practice in this field took root and developed due to the large wave of immigration from Germany (which arrived in the country in the wake of the Nazi party's rise to power) on one hand, and the escalation of the Jewish - Palestinian conflict on the other. During those years the Jewish establishment began to realize the potential embodied in the medium of photography, and in view of the growing national need for image-building material, started employing it extensively to promote the national goals. One aspect was, the establishment of a colonial language (that was influenced from the Western colonial photography in the Holy-Land in the 19th century), that served the Zionist enterprise. Jewish Photography had a key role in constructing, for example, the image of the “New Jew” in the new land, or how the Palestinians were presented. The Jewish establishment incorporated symbols that would accompany the Zionist ethos for many years to come and which would affect the representation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for many years. The book is also the first that deals extensively with the history of Palestinian photograph from late 19th century to mid- 20th century. It exposes, for the first time, cultural and photographic Palestinian treasures and archives that were looted or seized by organized Jewish/Israeli forces or by individuals - soldiers and civilians, as part of the pre-state and state colonial mechanism.

The Palestinian leadership, albeit united in its rejection of Jewish settlement, made little use of photography in its self-promotion campaign and in the campaign for the conflict’s image. Palestinian photography was individual photography, without any guiding hand, a fact especially evident vis-à-vis organized Jewish photography. The Palestinian photographer was a documenting photographer, an “anthropologist-photographer”, not politically active. Palestinian photography in the 1930s and 1940s was thus non-establishmental, and was created, for the most part, under independent commission circumstances, whether private or commercial, including both local and foreign press photography. It should be stressed that many Palestinian photographers followed in the footsteps of the Armenian photographers, who had established here, from the second half of the 19th century, a local photographic tradition. Toward the late 1940s various Palestinian photographers (non-organized individuals) began voicing a more explicit political stand, delving into the Jewish- Palestinian conflict and documenting its ramifications, images that were used in the Palestinian information camp. This tendency was intensified during the seventies, and mainly after the first Intifada (uprising), when still photography become a marketing and image-building tool in the hands of the secular Palestinian leadership.

The exhibition and book examines the roles and functions of each of these types of photography- The Western colonial photography of the 19th Century, Jewish (institutional and independent)) and Palestinian- in the public sphere, and their impact on a wider social and political spectrum. With regard to Jewish photography, the exhibition and the book trace the way photography, in all its varied manifestations, helped constitute both a colonial terminology (influenced by the Western colonial photography of the 19th century) and national terminology; and the way nationality “invented” itself visually in relation to parallel phenomena prevalent in the world at the time (in Russia, Germany, the United States). The show and the book explore the impact of still photography and cinema on the construction of images, symbols, and myths as part of the worldviews that shaped society. It features films made by still photographers who also engaged in cinema – as directors, photographers, and producers, investing their talents toward the promotion of the Zionist idea.

In addition, the exhibition and the book focus on independent experimental-avant-garde photography in the Jewish sector – the kind of photography channeled mainly toward commercial purposes or created out of an artistic approach, unrestricted by the dictates of commission. They refute the claim that at the time, photography was almost entirely Zionist-institutional. It sets out to demonstrate that experimental Jewish photography was created at the margins, which sought to expand the boundaries of photographic language and introduce cultural and other issues. It should be noted that in many cases, avant-garde photography evolved under the auspices of commercial photography, since the latter was free of institutional dictates, thus serving as fertile ground for experimentation and boundary-crossing works.

Reconstruction of the space where Helmar Lerski featured his series of Jewish Soldiers in the exhibition The Changed Face: A Land and a Nation in Fight and Work, The Keren Hayesod Art Show at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (1943), allowed me to present the type of photography that evolved on the borderline between avant-garde photography and institutional-propagandist photography. However, it is hard to make a clear-cut distinction between photographers according to the type of photography in which they engaged, since the majority of them worked for the Zionist national institutions as well as independently. The harsh living conditions forced them to take on virtually any work that came along. The style they developed was at times enlisted to service the establishment, at others, harnessed in favor of free market goals, and at yet others – employed in an entirely independent manner.

| | | | Zionist Institutional Photography in the 1930s and 1940s and Colonial Aspects | | | The Jewish establishment realized the potential inherent in the medium of photography for propaganda purposes and for visually conveying the Zionist ideal. Consequently, the departments of photography in the establishment’s information offices expanded considerably during the 1930s and 1940s, especially those of the funds (Jewish National Fund [JNF] and Keren Hayesod Foundation Fund) and the Jewish Agency. This tendency had a marked impact on the private and public language of photography which was evolving in the country during those years. Hence the funds’ key role in the local promotion of the photographic medium must be stressed, concurrent with the institutional backing it received elsewhere in the world (as in the case of Russia, the United States, etc.).

The funds established their photo services mainly in order to send informative-propagandist material abroad to be used in the Jewish press and in lectures aimed at fund-raising, prompting people to immigrate, and promoting the Zionist ideal. At the same time, the photographs also served the establishment for propaganda purposes in Israel and abroad, whether through the local and foreign press, or through other mass media means- exhibitions, posters, post-cards, stamps, and the like.

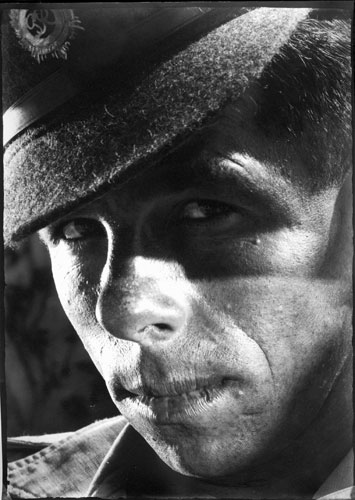

The institutional bodies sought through photography, cinema and graphic design, as well as through other media, to form a stereotypical heroic image of the New Jew in Eretz-Israel (Palestine): larger than life, with European features, lacking individual identity, constantly toiling. The image of the pioneer (the "halutz") who embodied the Zionist ideal, became an elitist, mythological symbol and the major image used by the workers’ movements and the national institutions to draw in new members. Since the late 1920s a clear Soviet influence is discernible in the institutions’ work methods: An attempt to construct an exemplary model of reality and of pioneering-civil-national utopias; pursuit of narrative photography via simple, clear photographs representing a coherent reality and accompanied by inscriptions, at times stories or essays, elaborating on their contents. In many cases the objects (mainly people or scenes) were photographed from an unusual angle – either very high or very low – in order to magnify and thus render them heroic. This type of photography generated images and ethoses as part of the Zionist perception, and was employed almost until the mid 1960s. The chosen subject matters recurred: proud soldiers (portraits of soldiers or images of marching soldiers), celebrations (the circle motif), contented, good-looking laborers at work or on their way to work, tilling the land with state-of-the-art equipment, watchtowers symbolizing the newly-erected self-defending settlements, etc.

In the course of time, many photographers adapted their work to the predominant ideology, creating a solid, non-critical Zionist-national terminology, even if they did not always identify with it. During those years, the establishment was the main work commissioner in the field, and many photographers were forced to adapt to the mainstream style which gradually crystallized. Only a few photographers tried to undermine the hegemonic line dictated by the funds, while various photographers who arrived in Eretz-Israel with a solid personal style harnessed it to national needs.

Zoltan Kluger (1895–1970s) seems to have been the quintessential institutional photographer, hence his extensive presence in this part of the show. Kluger, who while still in Germany exhibited outstanding photographic qualities, developed a style which was a cross of sorts between documentary and staged photography. This type of photography is also discernible in the work of other photographers, among them Yaakov Rosner. The subjects in these photographs were always handsome, strong, happy, and hard-working. When reality was incongruent with the expectations, it was staged in a pseudo-documentary fashion.

Concurrent with their activities in the field of still photography, many photographers in the country tried their hand at cinema as well, whether as photographers or as directors. The most outstanding among them were Helmar Lerski, Walter Kristeller, Naftali Avnon (Rubinstein), Tim Gidal, Lasar Dünner, Sasha Alexander, and Ellen Rosenberg (Auerbach). There is great similarity in the strategies they employed in still photography and in cinema.

| | | | Additional Colonial Aspects | | |

The Palestinian Other

The Zionist leadership belived that in order to establish its control over a conflict-ridden country and gain the support of international public opinion for the establishment of an independent Jewish state, it must, inter alia, establish an unequivocal self-promotion system. It used the infrastructure created by 19th century European photography as marketed in the western world, employing its perception of the Holy Land as biblical and as linked to the New Testament - a land where very little has changed (destitute and underdeveloped), as well as its attitude toward the “Oriental Other” (as backward, yet symbolizing biblical figures). European photography ‘delivered the goods’: an exotic, magical biblical-primitive Orient. The Zionist establishment used these colonial images, and others, for its own needs, and through the “undeveloped Other” shaped the “modern” identity of the New Jew in his land. The juxtaposition of sparse underdeveloped settlement and a vast settlement enterprise with distinct modern, western features, as well as the representation of a ruined, neglected, barren land waiting to be reclaimed – all these provided political power, especially since the bodies that were to decide on the question of the conflict between the two peoples were western. Furthermore, the use of the biblical image embodied a response to the question of historical right over the land.

The image of the “Palestinian other” in Jewish photography relied on two major unique colonial motifs: One was old-new/before-after, and the other – collaboration and enlightened neighborly relations with the Palestinians.

Old-New/Before-After

The funds, which represented the establishment, used to present settlements or areas in their quasi-primeval state: desolate, primitive, namely – in their pre-Zionist condition, and the change that occurred in them as a result of the Zionist settling enterprise. The past was identified with the primitive Palestinian, whereas the present – with the progressive, modern Jew. This was a prevalent strategy in exhibitions organized by the funds, reinforced via multiple means: photographs, comparative charts, and text, as well as films distributed in and outside of the country.

Collaboration and Enlightened Neighborly Relations with the Palestinians

The heads of the Zionist establishment often faced moral dilemmas spawned by Zionism. The funds, in their own way, manifested these conflicts. They sought, for example, to define the New Jew in relation to the backward Oriental other not only by creating a modern image, namely through knowledge, but also endeavored to create a moral image in their treatment of that other. Much effort was invested in emphasizing co-existence with the Palestinians, while concealing the fact that Jewish settlement may or does offend the Palestinian people, as well as the very existence of a conflict with the Palestinian population.

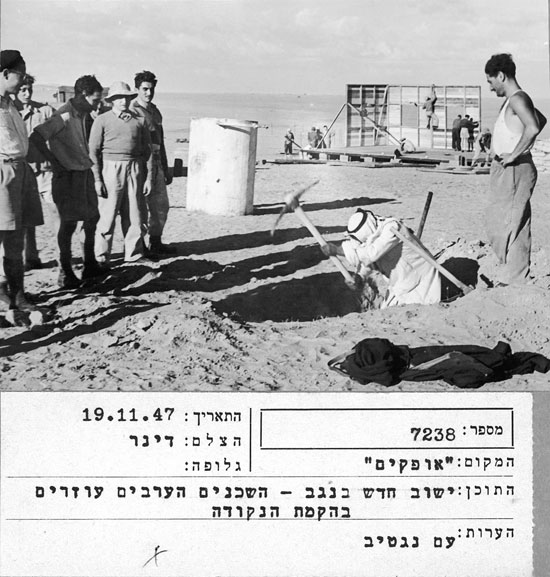

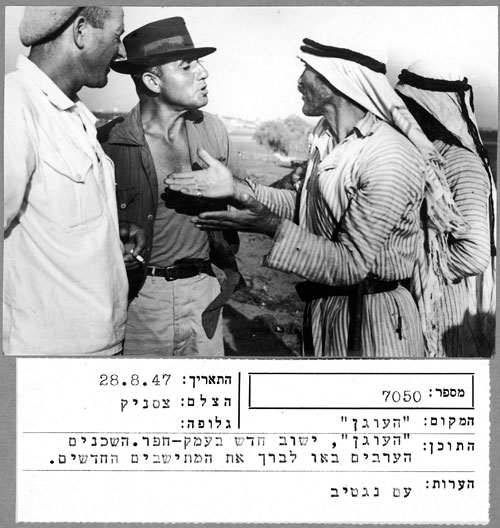

Many photographs depict the good, enlightened neighborly relations maintained by the Jewish settlers with the Palestinians, the cultural, social and economic assistance they gave their needy neighbors, and the profit gained by the Palestinians from the Jewish settlement. They preferred to present the conflict in the country from a perspective of dual development – side by side – of a primitive Palestinian society and a modern, moral, supportive Jewish society. Many photographs portray Jewish-Palestinian coexistence on the mundane level: the joint Jewish-Arab bus line Tel Aviv-Jerusalem-Beirut, the joint May Day Procession in Ramla (with signs in Hebrew, Yiddish, and Arabic), Jews teaching Palestinians to fight off the malaria-carrying mosquitoes, etc. In like manner, the texts accompanying the photographs further expose and reinforce this tendency. The funds used titles and inscriptions to establish the desired message, and prevent any possibility of obscurity: The Palestinians give the Jews water, visit them, help them erect a fence for a new settlement, help them build that settlement, greet the soldiers, and in the most problematic case – “curiously follow the neighbors’ labor”.

| | | | The Exhibition The Changed Face: A Land and a Nation in Fight and Work | | | The exhibition The Changed Face: A Land and a Nation in Fight and Work, The Keren Hayesod Art Show was held at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1943. It highlights the question of photographers’ awareness to the use made of their work by the establishment. It serves as an important case study, for it was exhibited in an art museum, thus going beyond the framework of propagandist shows extensively presented up until then in non-museal public spaces. This is one of the only times where a portion of a propaganda show was exhibited as fine art: individual photographs, indication of the “artist”-photographer’s name, hanging discrete images in fixed intervals in a white cubic space, etc. At the same time, other spaces of the exhibition continued the funds’ propaganda exhibitions tradition: Biblical texts discussing the redemption of the land, charts and tables indicating the country’s development as a result of Jewish settlement (for instance, the number of inhabitants or the per capita income before and after the Zionist enterprise), statistic data, photographic montages constructed on large-scale plates, creating a new narrative. The plaques comprised a multiplicity of photographs, while cropping the works and without mention of the photographers’ names. The exhibition also featured aerial photographs by Zoltan Kluger, portraying the development of the settlements (“before-after”), as well as sculptures of a typical pioneer and of Haim Weizmann.

At the beginning of 1942 Keren Heyesod Foundation Fund approached the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, requesting that an exhibition be held on the premises. The museum directorate had reservations on account of the show’s propagandist rather than artistic nature. Keren Hayesod responded as follows: “We, on our part, have no intention of concealing our propagandist purpose. However, since certain fears have surfaced, we must stress that we wish to present our propaganda in a highly artistic manner… This may be indicated by the considerable space given in the exhibition to Helmar Lerski’s portrait photographs… We emphasize this since the major part of our exhibition will consist of artistic photographs, thus we would like to refute the claim that it interferes with the artistic dimension of our show.” The instruction book for the exhibition guides read: “The exhibition endeavors to show the changes that occurred in the appearance of the land and the people since the beginning of its settlement by the Jewish Agency and Keren Hayesod Foundation Fund.”

| | | | Avant-Garde Currents in Independent Jewish Photography | | | The exhibition sets out to refute the claim that photography at the time in question was, for the most part, oriented toward the Zionist establishment. It features the avant-garde, experimental-independent Jewish photography which was channeled to commercial purposes (including advertising and industrial photography), or created in an “artistic” mode, liberated from the dictates of its commission circumstances. Avant-garde photography developed in many cases under the auspices of commercial photography since the latter was free of institutional dictates, thus providing fertile ground for experimentation and creation of boundary-crossing works. At the margins, independent “artistic” experimental photography gradually developed, which sought to expand the boundaries of the language of photography.

The majority of photographers from Germany and Central Europe who operated in Eretz-Israel during the 1930s and 1940s were influenced, as aforesaid, by the avant-garde currents in German art of the late 1920s and early 1930s. This is one of the reasons that the use of the photographic image in local Jewish society flourished during those years. Some of the photographers who operated in the country were art school graduates (Comeriner, Avnon, Schwerin, and Raviv-Vorobeichic [Moï Ver]), some had an active photography studio in Germany (Comeriner, Kluger, Rosenberg), and some, as aforementioned, won acclaim while still abroad (Lerski, Comeriner, Gidal, Raviv, Kluger, Kristeller). This part of the exhibition features work created by the same photographers in Germany and in Israel. Concurrently, photographers with no background or education in the field arrived in the country, developing a local experimental photographic language.

As in Germany, here too, the values of New Photography and an unmediated and liberated approach to it have developed conspicuously, mainly in the field of commercial photography (following Renger-Patzsch and Hans Finsler). This is evident in particular in the work of Alfons Himmelreich, Alfred Bernheim, Marli Shamir, and others, especially in the close-ups, in maintaining the object’s fundamental form detached from its surroundings, and in setting high visual standards. Just as discernible is the impact of photographers who, while still in Germany, engaged in photography in the fields of advertising and mass media, establishing these types of photographic practice in their new country: Erich Comeriner, Walter Kristeller, Errell (Richard Levy), Ellen Rosenberg (Auerbach), Tim Gidal, Moshé Raviv Vorobeichic (Moï Ver), and others. Further areas in the field of advertising and mass media manifested in local photography were montage and typography (Comeriner, Errell, Raviv) and commercial cinema photography (e.g. Kristeller’s commercial film Sova Bread). And there were still other areas: dance photography (Himmelreich and Alexander), theater photography (Isaac Kalter and Sasha Alexander), and a new type of press photography (Walter Zadek and Tim Gidal).

| | | | Palestinian Photography | | | Palestinian Photography in the 1930s and 1940s, albeit essentially direct and documentary, was individual photography, unorganized for the most part, which played in the early period a very small part in the battle for the image of the conflict between the two peoples ( besides, Karimeh Abbud who defined herself in 1924 as ‘the only nationalist photographer’ [El-Carmel, 7 February 1924]). The local Palestinian leadership, although united in its opposition to the local Jewish settlement, made little use of photography as a tool in its self-promotion campaign for reasons yet to be explored. Local Palestinian photography was mainly created under commission circumstances both private and commercial (studio photographs, family photographs, landscape photography, special events, etc.), including press photography for the local and the foreign press. The Palestinian photographer functioned as an “anthropologist-photographer,” travelling throughout Palestine depicting its landscapes, inhabitants and their customs, and was not politically-involved. He/she operated as an independent photographer, and was free of institutional dictates.

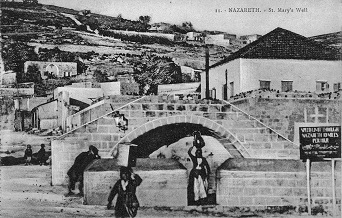

Concurrently, photography smacking of nationalism was also created in Palestine, which could be employed in the Palestinian information campaign. It was, probably, influenced by the local Palestinian national revival and perhaps even by Jewish photography which at the time enjoyed prosperity and wide circulation. The radiant young man holding grain in the field, or the young beautiful girl from Bethlehem sipping the country’s living water against the backdrop of the land’s glorious past – such images, although not photographed out of national propagandist intentions, attest to national revival. Many other photographs present life in Palestine: commerce, agriculture, culture, etc., reflecting active, lively, productive life in the country. These photographs have the power to contradict the claim about a deserted, barren, neglected, underdeveloped land which must be “reclaimed” and “redeemed”. An information system aware of the photographic medium and its communicative power might have utilized these photographs in its national struggle as well. The central first Palestinian photographers that were active in the period were Chalil (Khalil) Raad, Daoud Sabounji, Fadil Saba and Karimeh Abbud (the first Palestinian woman photographer whose work was in dialogue with Saba). Among the Armenian photographers active in the Palestinian public realm one should mention Elia Kahvedijan and Hrnat Nakashian (after he was exiled in 1948 to Gaza, he worked with his brother in law Kegham).

| | | Various Palestinian photographers were also influenced by 19th century European photography, which sought to bring the exotic, romantic, magical and alluring Orient to the West. For the western world, it was a backward, underdeveloped, conquerable place. Many photographs by Palestinian photographers bring to mind scenes from the New Testament (for example, Mary and the infant in Bethlehem or Nazareth, or in the inscriptions accompanying various photographs). Even though they were probably taken out of mere commercial considerations – to meet the growing European demand for photographs of the holy sites, and for views and scenes of the biblical Holy Land – one cannot disregard the associations they evoked.

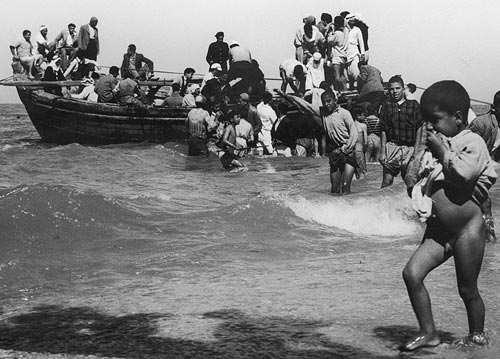

Toward the late 1940s the awareness of individual photographers become more acute, even if they still operated in an independent, disorganized manner. Many of them began documenting the conflict between the two peoples which intensified toward 1948, and its repercussions (especially Chalil Rissas [Khalil Rassas] and Ali Za'arour [who was active from an earliest period]). Many photographs depict Arab and Palestinian soldiers in action, during marches, lineups, gatherings, etc. Others portray, on one hand, the damages inflicted on the Jews: demolished houses, Palestinians/Arabs looting Jewish property, Jewish convoys being attacked and wounded, etc., and the issue of the Palestinian refugees on the other. These images were used largely in the press to meet national goals.

In order to sketch a full picture of the Palestinian world in those years, the outstanding photographers of the time are presented, alongside photographs from the late 19th century/early 20th century (Chalil [Khalil] Raad from Jerusalem and Karimeh Abbud from Beith-Lehem) and the late 1940s-early 1950s (Hrnat Nakashian from Gaza).

The book exposes, for the first time, Palestinian materials in Israeli archives and their seizure/looting by the colonizer.

| | | | For more information about Elia Kahvedijan | | | | For more information about Chalil Raad | | | | Ali Za‘arur: Early Palestinian Photojournalism, the Archive of Occupation and the Return of Palestinian Material to Their Owners, Jerusalem Quarterly 74, 2018: 48-56 | | | | Interview, Jaffa, The Orange's Clockwork, Documentary Film, Eyal Sivan (director), 2009 | | |

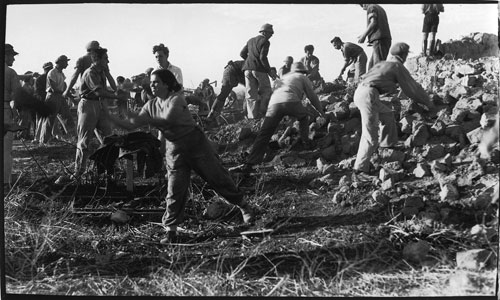

| | | |  | | Zoltan Kluger, Fruits of the land, 1940s, State Archives | | |  | | Zoltan Kluger, Girl from Kfar Vitkin in a wheat field, JNFArchive | | |  | | Hannah Safieh, Harvest, 1930s, Courtesy of Raffi Safieh | | |  | | Avraham Malavsky, To work, 1937, JNF Archive | | |  | | Zoltan Kluger, Sport, 1940s, State Archives | | |  | | Zoltan Kluger, Jewish Soldier, 1945, JNF Archive | | |  | | Lazar Dunner, Jewish Soldiers marching, 1941, JNF Archive | | |  | | Avraham Malavsky, ''Settling day – joint effort'', Kfar Rupin, 1938, JNF Archive

| | |  | | Lazar Dϋnner, Ofakim, New settlement in the Negev - Arab neighbors help in establishing the outpost, 19.11.1947, JNF Archive

(translated from the typed caption)

| | |  | | Fred Czasnik, Ha’ogen - new settlement in Emek-Hefer. Arab neighbors come to greet the new settlers, 28.8.1947, JNF Archive

(translated from the typed caption)

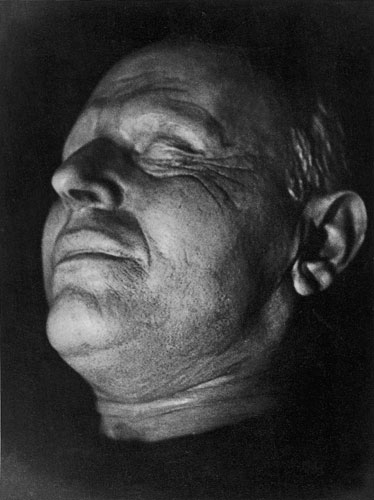

| | |  | | Helmar Lerski, From the series Jewish Soldiers, 1942-1943, the series was shown at the exhibition The Changed Face, Courtesy Yoav Marom | | |  | | Kurt Triest

Untitled , 1940s (?), Courtesy Ilan Roth

| | |  | | Tim Gidal, Chaim Nachman Bialik, Death Mask, 1935, Courtesy Pia Gidal

| | |  | | Karimeh Abbud, Nazareth, undated (1920?) | | |  | | Hrnat Nakashian, Refugees, Gaza, late 1940s-early 1950s, Courtesy Saro Nakashian | | |  | | Ali Za'arour, Palestinian Refugees in an Olive Grove, 1948, Courtesy Zaki Zaarour | | | ![studio rissas (rassas, ibrahim rassas, chalil [khalil] rassas), fighters, 1948](http://www.ronasela.com/_BackOffice/ContentImages/en/C854775.jpg) | | Studio Rissas (Rassas, Ibrahim Rassas, Chalil [Khalil] Rassas), Fighters, 1948 | | |

|