| Species of Memory: Notes on the Works of Roi Kuper, 1990–2001 | | | During the last decade of activity Roi Kuper has created three main series: Vanishing Zones (1990–1994), Necropolis (1996–2000), and Citrus (1999–2001). Although at first these series seem very different from each other their inner syntax is similar, forming a closed, coherent body of works. An examination of the content reveals “a dream a somnambulist illusion of his semi-somnolent consciousness” in the words of Danilo KiŠ in Enciklopedija Mrtvih (Encyclopedia of the Dead) [1]. The subject matters in Kuper’s works are hard, incisive, painful, yet the visual stamp he puts on them is not offensive or garish, but beautiful, pleasant, gentle. Kuper’s gaze is introverted and the calm surface of his works has to be peeled away to reach the heart of the matter.

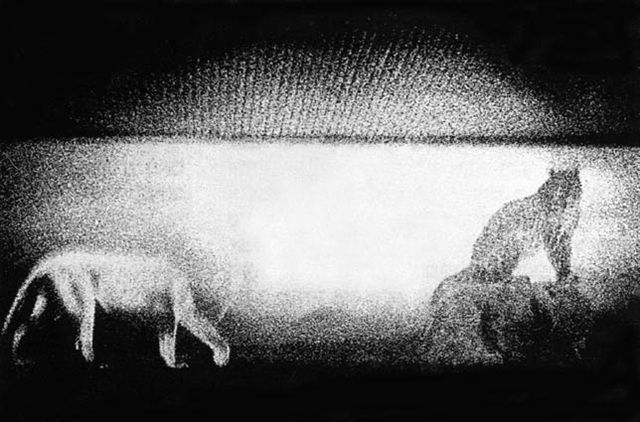

The first series, Vanishing Zones, was photographed with a toy throwaway camera, the kind containing very small films. Kuper’s process was to first print the images taken by the camera and then to separate the photographic paper into its layers; he peeled away layers from the photographic paper until he reached a level of translucency, which could be used in his work as a new negative. The process of separating the external surfaces of the paper (the emulsion, the uppermost layer) from the inner layers was difficult and demanded special treatment, the control over the production of the “new negative” was limited, for the paper had a tendency to tear and disintegrate. More over, in order to produce the “new negative” Kuper printed a contact from the peeled upper layer of paper. Thus it became its own negative, which was then also peeled, and again, he printed an image from it. The process was done again and again, each time more and more details of the original image disappearing, until its total disintegration. Sometimes Kuper would scrape the new negative and damage it, so that details would vanish and texture would be added, and sometimes he left the negative soaking for days in water, or placed it specifically in a place with “bad” conditions, so that the negative would be damaged and mutilated to the desired point of disintegration of the image. Kuper made a decisive choice to work with a negative of translucent and disintegrating paper – the paper fibers of the negative were also picked up in the print process and added to the effect of dimness and mistiness that the artist aimed for.

Kuper decided to neglect the sanctified practices of photography that ruled during the 1980s – the years of modernism in Israeli photography (the “decisive moment” of photography, “correct” photography, the “correct” exposure, the “correct” print, the search for the perfect composition and so forth) – for “rebel” photography that allowed him to focus on personal and spiritual processes. In some ways Kuper was connected to the wave of personal and experiential photography of the eighties, one of whose common characteristics was photography within the “family territory” (for example Simcha Shirman in Acre, Oded Yedaya in his close environment, and Boaz Tal who set up scenes from art history in his house) – a form of photography that exempted the photographer from dealing with an external reality. But in opposition to this wave, Kuper began a process of breaking free of the formalism of classic photography and its hallowed conventions. He tried to distance himself from the aesthetic idealism and modernist judgment of a work of art, to get rid of the aura of the surrounding photographic image and break through the framework of the immanent discourse in the field. Kuper chose not to use a technical camera, or a professional-conventional one, but preferred a throwaway toy camera of the type sold in photography shops for a few shekels to any passing customer, which are known for the low quality printed images they produce. He chose to connect to the “low” qualities of the photographic process and to accentuate them, so that in a homemade process he created negatives from peeled paper, a replacement of the professional celluloid negative. The use of the peeled paper negative, which because of its repeated peeling and use became torn, added to the mistiness of the images and distanced them from any “correct” photographic convention. Kuper states that during those years he had a model of photographic works that expressed a negation of the accepted stream of Israeli photography [2]. He mentions, for example, the work of Dalia Amotz in Israel, who intentionally photographed into the sun and “burnt” large parts of the negative, and the series by the American Robert Frank shot with a Polaroid camera, where the photographer wrote above each picture phrases such as “Be Happy,” New Year’s Day, 1981,” “holy,” and “Suck of Hell.” He came across these photographic works before Vanishing Zones and they formed a mindset for creating the series, which Kuper mulled over for a few years. In the series he produced virtual images – at the time it was called “manipulated photography” – things from his immediate environment: friends, family, objects and views, whose natures were a sort of dark and elusive memory of a moment or continuing situation. As opposed to the frozen photograph on a conventional negative, the photographs in the series carry with them the feeling of extended time, as if created in the darkroom of the subconscious. These images reflect a gradual process of the disappearing and blurring of details, and to an extent they correspond to the gradual disappearance of images in personal memory. Yet even though the roots of Kuper’s works are in personal memory, they deal with the full scope of the subject of memory, disappearance, hybridization, and disintegration in terms of the collective-archetypical. Creativity, expressiveness, and mysticism are all clearly present in Kuper’s works, with the influence of European artists dealing with trauma related memory who also present the image in its physical reality, such as Christian Boltanski. Vanishing Zones is the first important series of photographs created by Kuper after his studies at the Hadassah College in Jerusalem (1980–82) and at the State Art Teachers Training College, Ramat HaSharon (1983–84).

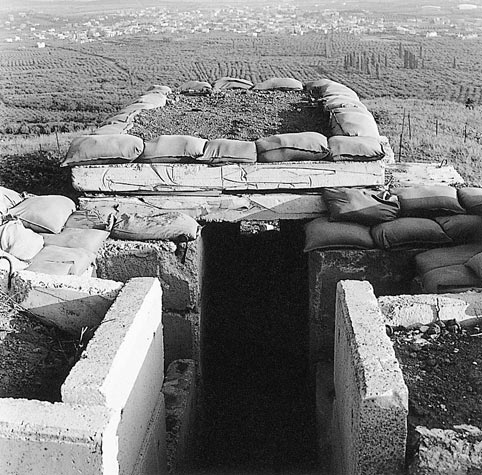

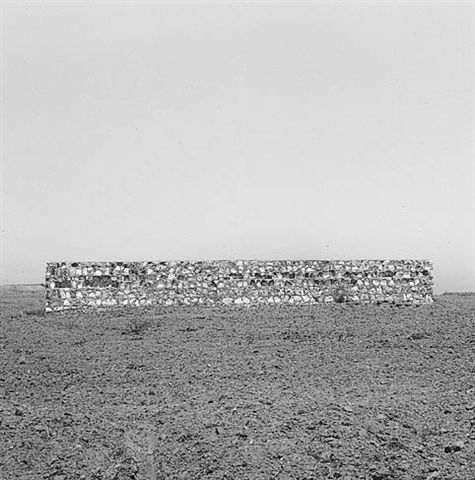

In 1996 Kuper made an important step toward a series of works with political and critical dimensions at its center. He paired up with Gilad Ophir, left the studio for work based mainly in the public space, and together with Ophir created the series Necropolis [3]. He abandoned “manipulated photography” for direct photography, sharp and untouched, of buildings and active and abandoned military bases. The small plastic throwaway cameras were dropped and exchanged for medium format cameras that used 6X6 cm. film, allowing high quality photography and prints.

Kuper’s move from a private, studio environment to a public, outdoor environment included poignant messages about the Israeli reality. With Necropolis – meaning “City of the Dead,” (for example burial sites in the suburbs of past civilizations, such as Egypt and Rome) – Kuper points out the Israeli “Cities of the Dead”: abandoned military structures, or buildings and complexes built to military specifications for exercises in urban warfare, yet situated in isolated and distant locations. These structures become quasi-monuments of Israeli history; in the past they were monuments to heroism, today they are neglected, miserable and ugly. Firing ranges empty of people and activity; abandoned camps; erect and isolated watch towers; buildings riddled with bullet holes used to practice urban warfare; radars; concrete surfaces (left both by the British army during the Mandate and the I.D.F.) that in the past had tin buildings, huts and tents placed on them, and are now covered by the desert sand; military structures, mainly built of asbestos (by the I.D.F.); and military structures of stone and concrete (of the Syrian and Jordanian armies) – all these look like ghost towns, corpses, shadows of a previous reality, vanishing (and memory) zones of forgotten places. All these places are reminiscent of archeological sites, even though some of them are active sites, especially those intended for military exercises of urban warfare, photographed when there is no activity, so they seem abandoned and neglected. To an extent they are suggestive of Bunker Archeology by Paul Virilio who during the years 1957–65 investigated defense plans and photographed bunkers and fortification systems set up along the French Atlantic coast during World War II. Virilio’s investigation dealt with the military sphere in Europe and its relation to the civilian sphere. An important part of his research and documentation was photographs of the bunkers and fortification systems [4]. The military bunkers in Virilio’s documentation seem to be full of glory and splendor, while the military camps and installations photographed by Kuper are expressly unheroic sites, and we are used to passing them by without acknowledging their existence. These structures and installations, hollow, decayed, riddled with bullets, deserted, are used by Kuper in his work dealing with the Israeli militarism that has penetrated many parts of Israeli society in a way seen natural by most Israelis. In his work he mainly relates to the expropriation of spaces and landscapes and their universal and pastoral value to military needs and an aggressive military presence. A glorious landscape expropriated for military needs, destroyed by the military’s activities and turned into an alienated, neglected and desolate place. The anti-aesthetic of military camps is accentuated by their being turned into ghost towns, as if nature itself has expelled them from within. The camps, that in the past broadcast strength, seem to be a science fiction film set forgotten in the desert. It isn’t surprising that the closed circle, with no opening, symbolizing the complete and the absolute, the center, occurs in different forms throughout the Necropolis series: the circle of an abandoned army post, where nothing grows within that seems to sketch itself in the heart of the virgin field – silent witness to the structure placed there in the past, or to activity held in the field in the past that prevents the growth of wild grasses inside the circle; or a ring encompassing a building, used for practicing urban warfare, and more. The circle that symbolizes perfection, the total, unity, is in many ways the circle of the Israeli collective that Kuper tries to examine to see if it has been breached.

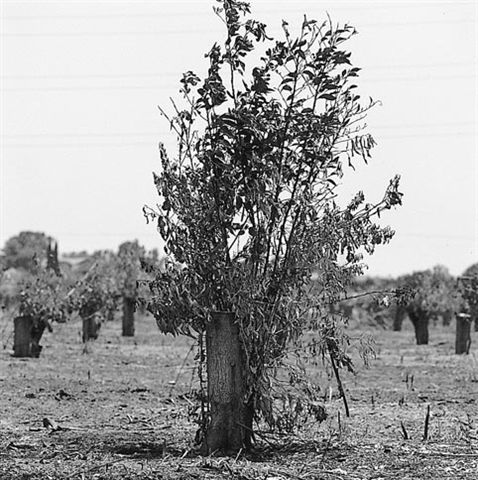

In the series Citrus, Kuper returned to independent work and ceased joint works with Gilad Ophir. He continued his work in public spaces with social, political, and cultural meaning, but his point of reference became more personal. He focuses on the photographing of deserted citrus groves and the disintegration and degeneration of the living body – the tree, the grove – that until recently was the absolute symbol of the Zionist dream of building the land and making it prosper by means of settlements and the economy. He starts with the image of a single tree, a separate entity that in the past was part of a flourishing and fruit-giving orchard, and now stands dying; its innards empty, and all that is left is its external bark. From the lone tree Kuper proceeds to describe a “living” grove, open space and landscapes, which also seem in many cases to be dying a slow, continuous death – until the edge of the settlement can be seen. Shortly before the groves become real estate plots, quick money earners for contractors and businesses, Kuper captures on camera what was once seen as the jewel in the crown of working settlements in Israel. He shows in one swoop the “living” and the “dead”: the rotting fruit tree, that was until recently living, or the tree and grove deliberately neglected, to prepare the land for the building of villas, condominiums, road systems, malls, and the like. The artificial extinction, or the slow-natural one preceding uprooting – the felled branches, the dry leaves, the signs of poison – are sharpened by the towns, sparkling here and there in the background and approaching the groves. For Kuper it is also important to photograph groves that, although they have been recently planted, seem to him fictitious. He sees in them as well, the shattering of the Zionist concept that presented the citrus grove as a symbol of new life full of hope in the country, as poetically described in Nahum Guttman’s Path of the Orange Peels. According to Kuper, the change in the way we relate to the groves in Israel is fundamental to a change in our worldview and symbolizes complex processes of a distancing from the national collective ethos toward a pure individualism. The orange, symbol of fertility and love, the “golden apple,” that sucks life from the sun, the fruit whose orange color symbolizes fire and creativity , has had its vitality taken from it in a reality of vulgar materialism. His memory of an independent and creative life in the old-new Hebrew land seems today a dull and immaterial memory, fading and forgotten.

All the series, as different as they may seem from each other in terms of material and presentation, deal with a single category of subject matter that has always occupied Kuper: hybridization, loss, and personal or public disintegration. In a long and slow process, influenced also by art trends in Israel and abroad, Kuper began dealing with these issues through contact with personal material amongst his close social circle, and then departing from the close circles surrounding him, he moved to the treatment of local and collective subjects. At first the image disintegrated with the disintegration of the photographic paper itself in a way that carried a statement that can only be understood one way; the object of the photograph is as the name of the series Vanishing Zones implies, expendable and ephemeral like the actual loss of the material. Later, in Necropolis and Citrus, the images themselves are concrete, sharp and clear, the prints beautiful, almost perfect, yet they show, in contrast to their physicality, processes of malignant change and deterioration in Israeli society. In Necropolis Kuper points out the erosion of militaristic might – the glue that holds Israeli society together and has controlled it since conception – through the display of military sites that have been abandoned or are no longer in active use, and sites for exercises in urban warfare that look as if they are deserted. They are cracked, about to collapse and dilapidated, their outlines blurred, and they seem to blend in with the desert, where most of them are placed. The desert, whose historic-symbolic meaning for the People of Israel was always a central axis, represents in its contemporary appearance the ephemeral. The desert winds seem to erode the buildings and military structures to the point of their merging with the desert landscape, until no memory is left of them, ideologically or conceptually. In Citrus, Kuper deals with the most offensive deterioration of the Zionist dream. From the start of Zionism in Eretz Israel, citrus groves symbolized the birth of the new Jew in his own country who worked the land and engaged in productive activity – as opposed to the Diaspora Jew. He built the country himself with pride and made its desert bloom through his vision. The blossoming groves that gave abundant fruit that was also marketed abroad and was a profitable industry, symbolized the realization of the Zionist dream. Happy youths picking oranges with joy and pride became a local and international symbol of the realization of the Zionist idea. Yet in the groves exhibited by Kuper nothing is left of all that. The groves become plots of real estate intended for development and accelerated building, and the city that had been so far away, cruelly bites into them. The photographs of the series were taken mainly in the south of the country, since the citrus growers are forced to move south as the land in the center of the country becomes more expensive. The barren, neglected, desert land of Necropolis, and the groves destined for uprooting are, therefore, the desert of Roi Kuper and Israeli society.

The disintegration in the works of Kuper is again, a single image symbolizing the collective. Kuper states that his interest lies mainly in a precise observation of details, in allowing the general to emerge from the individual. As Georges Perec in Species of Other Spaces and Other Pieces [5] (Kuper claims to be influenced by him) moves from the description of the most banal detail (the page) described in great precision, to a systematic description of spaces larger than him that encompass him – the room, the apartment, the apartment building, the street, the neighborhood, the town, the country, the world, space, a place that can not be inhabited – Kuper focuses on the detail, the single image: the leaf, the branch, the single tree, the grove, the field, the space of Israeli reality. Perec places the memory of his room on writing paper, while Kuper places his memories and impressions on photographic paper. “The resurrected space of the bedroom is enough to bring back to life, to recall, to revive memories, the most fleeting and anodyne along with the most essential. The coenesthetic certainty of my body on the bed, the topographical certainty of the bed in the room, these alone reactivate my memory, and give it an acuity and a precision it hardly ever has otherwise. Just as the word brought back from a dream can, almost before it is written down, restore a whole memory of the dream, here, the mere fact of knowing…, that the wall was on my right, the door handle beside me on the left…, the window facing me, instantly evokes in me a chaotic flood of details so vivid as to leave me speechless…” [6]. Kuper wanders restlessly through the disappearing military sites and citrus groves; each and every one of these sites includes countless “Israeli” details. He focuses on the crumbling, pockmarked, abandoned building, covered in desert dust, and on the “living” and “dying” fruit tree. He presents in detail and with obsessive precision the way the tree – or the building – becomes hollow from within, miserable in appearance, or given to processes of abandonment and death that overcome them. The dry, isolated branches; the final blossom; the destroyed wall; the deserted field; the injured landscape; the living tree, neglected in the virgin land, with wild grasses and parasitical plants climbing over it and suffocating it – these and others are examples are captured time and again by his camera. The single tree, so often photographed with a white, blinding line dividing it from the horizon, or the building photographed countless times from almost every angle, attest to his striving to discover something from a vanished truth. The distant and forgotten citrus grove, hinting at the many hopes pinned on it; military sites, in the past sites of power and energetic activity, and today standing haggard and eroded; or the lone tree, once lovingly taken care of through pure belief, which blossomed and bore fruit, and now neglected and exposed to damage and destruction by nature or man – all these tell of a collective return to the story of the desert according to Kuper.

Although it seems that Kuper’s work is created with mental and emotional control and command, he emphasizes that like The Man Without Qualities [7] he wanders through the expanses of life and touches the things he encounters on the way. His flow is in his words, both controlled and not controlled, aware but to a large extent random as well, rational yet emotional. Like a flaneur wandering with no planned destination, he too wanders through the sphere of the Israeli and desert-like reality, until he comes across something that attracts his attention – and there he stops a moment, examines, ponders. Indeed, shortly he will detach himself from it, for something else will distract him, and he will turn to it and will remain with it for a while. The destination is not planned ahead of time, so it can be summarily changed, but when something attracts Kuper’s attention, he will stop to check it out, and let it contain him | | | | Notes | | | 1. Danilo KiŠ, Encyclopedia of the Dead, Faber and Faber, 1990 (translated by Michael Henry Heim) p.79. The book was originally published in Serbo-Croatian in 1989.

2. From conversations with the artist, October 2000 – January 2001.

3. Kuper and Ophir traveled together throughout the country, talking, exchanging ideas, thoughts and impressions and having joint experiences, but each, according to Kuper, worked and photographed alone.

4. Paul Virilio, Bunker Archeology, Les Editions du Demi-Cercle, 1999. The book was originally published in 1975.

5. Georges Perec, Species of Other Spaces and Other Pieces, Penguin, 1997 (translated by John Sturrock). The book was originally published in French in 1974.

6. Perec, pp. 21-22.

7. Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities, Coward-McCann; New York, 1953 (translated by Eithne Wilkins and Ernst Kaiser). The book was originally published in German in 1930.

| | | | For the photographer web-site | | | | For Noga gallery web site | | |

| | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Vanishing Zones, 1990–1994, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Vanishing Zones, 1990–1994, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Necropolis, 1996–2000, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Necropolis, 1996–2000, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Necropolis, 1996–2000, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Necropolis, 1996–2000, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Necropolis, 1996–2000, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Necropolis, 1996–2000, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Citrus, 1999–2001, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Citrus, 1999–2001, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Citrus, 1999–2001, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Citrus, 1999–2001, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |

|