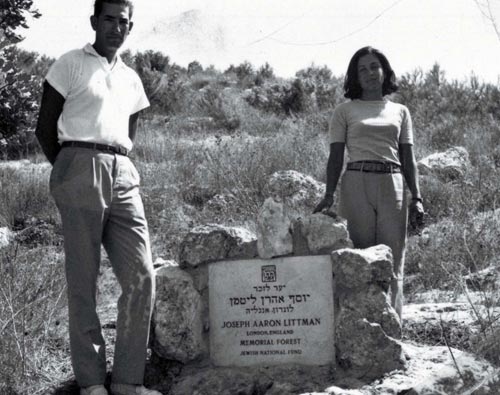

| "White Land or after the 'Forbidden Forest,' 1967-2001", in: Ariane Littman, White Land, The Artists House, Jerusalem, 2001 (text for exhibition catalogue) | | | | In 1967 the Littman’s, an Anglo-Jewish family residing in Switzerland, donated, for Zionist reasons, money to the Jewish National Fund in order to have a forest planted in the memory of their grandfather, Joseph Aaron Littman – Ariane Littman-Cohen’s father’s father. A few short weeks after the end of the Six Day War the forest was planted in Nahal Sorek, close to Bet Shemesh. The Littman family’s donation was added to donations from British Jews; the forest which grew and spread, was called Yishi Forest, because of its proximity to the Yishi Moshav. | | | | Action No. 1, 1992 | | | | Within the framework of her exhibition Nature Morte (Bograshov Gallery, Tel Aviv) which dealt with the interaction between culture and nature, Ariane Littman went out to look for both the forest that had been planted in her grandfather’s memory, and the memorial plaque situated there. She got in touch with the Jewish National Fund (JNF), whose employees found the location of the forest on a map. They drove Littman out to the forest, and it was then that she discovered that the forest was camouflage for a secret military camp, and that access to the forest and to the memorial stone was forbidden. Since then she has called it the “Forbidden Forest.” In the exhibition she exhibited, amongst other things, a replica of the memorial plaque, prepared for her by the Jewish National Fund. | | | | Action No. 2, 1997 | | | | As part of the exhibition Out of Sense (MUKHA Museum, Antwerp, Belgium) Littman exhibited an additional replica of her grandfather’s memorial plaque. At the same time she initiated another action: she asked to appropriate a new portion of forest, according to her choice, in memory of her grandfather, where she could place a new memorial plaque [1]. It was intended to thus fulfill the original aim of the forest, as foreseen by the artists family when they decided to make a sizable donation to the JNF. The forest would be both a memorial site and a place of leisure and being at one with nature. Littman chose to place the memorial plaque ten minutes away from the, in her words, threatening “Forbidden Forest.” The plaque was set in a place where soft seedlings had recently been planted [2], close to the blooming Judas trees. | | | | Action No. 3, 2000–2001 | | | Littman began to look for aerial photographs of the “Forbidden Forest” – both historical photographs of the area and photographs from recent years. Backed by the documentation she hoped to find answers to the questions which had been bothering her since 1997: When did the forest become “forbidden,” since when has it been part of a military base? Was there a connection between the mature forest, after the trees had grown, and its role of concealing the base – maybe the area had been designated from an early stage to be a military base, and the forest was planted for state reasons, thus deceiving the donors, whose money was not used as requested? Why were the families and donors not notified that the forest had become “forbidden”? The above notwithstanding, Littman-Cohen acted through personal considerations, for example the voyeuristic impulse to look at the “Forbidden Forest,” which she had never seen, and would probably never see. It distressed her that she was prevented from reaching the forest, a place that for her was supposed to be personal and intimate, a place for her to bring her children and tell them stories of her grandfather and his life.

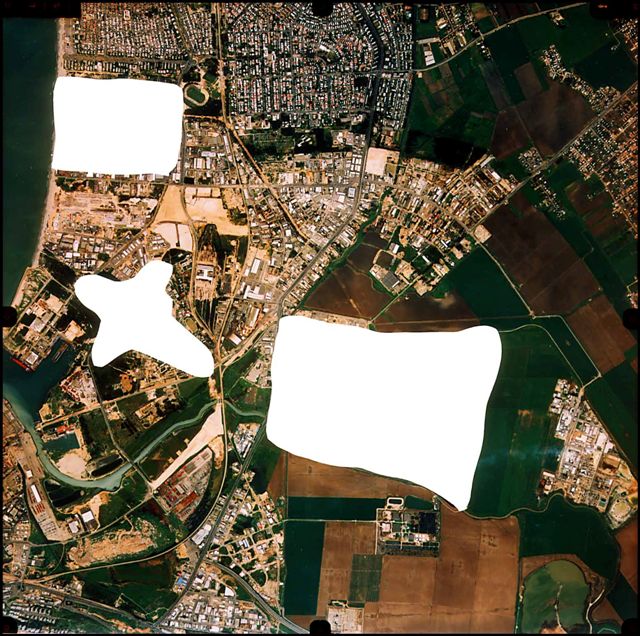

All this led Littman to the JNF archives to look for correspondence, photographs, and maps; and to the Panorama – Imaging Technology archives, there it became clear to her that the “Forbidden Forest” was only one of many “forbidden areas”. The forest had been erased at the orders of the Military Censor, and in its place was left a large white stain. And so her hopes to see an image of the forest from above were dashed. Usually the stains on these photographs are filled in by Panorama – Imaging Technology with images such as pools, trees, paths, roads, houses and the like, but she decided to leave the emptiness – the white stain – emphasized and empowered in its symbolism: the realm of desire whose access is blocked from her, taken from her and concealed from her, and her family.

Driven by this desire Littman-Cohen reached [The] White Land. With determination and obsession she began to build a map of Israel, made up of innumerable “white holes.” In a way similar to the puzzle work Mother and Daughter, 1963, 1994 – an attempt to trace a personal memory through the assembly of thousands of pieces that make up an old personal photograph –the artist tries to build a contemporary puzzle of the Holy Land through the aerial photographs. But it is created with the viewer’s awareness of the totality of the “white holes,” the areas that segment the continuity of the map of Israel. As in the work Mother and Daughter, 1963, anchored in personal memory, so White Land, 2001 is based in the personal and private experiences and desires of Littman-Cohen, but touch on the collective experience and existence.

| | | | Pilgrim in White Land | | | Ariane Littman grew up in Switzerland and was educated in a Catholic school, in the lap of the Christian tradition. She states that this was one of the central reasons that led to her extended occupation and research of the concept “Holy Land”: “The concept ‘Holy Land’ is meaningless for most Israelis. I grew up surrounded by longing for the Holy Land, the land of Jesus. Like the pilgrims who came here during the Nineteenth Century, and looked for meanings and clues to the life of Jesus in every tree and shrub, I was also entranced by the symbolism of the subject and the romantic ideology of the Holy Land. Even though I came to Israel for Zionist reasons, my point of view, at least at the beginning, couldn’t be freed from the place where Christianity observes the Holy Land, like a tourist, from outside. Over the years, as I have become more and more Israeli, the dream has been destroyed by its conflict with reality, and my observation has become critical, immanent to the place. The work Invitation to a Voyage, 1993, which is the first work to deal with the subject of the Holy Land, was displayed in the exhibition The Range of Realism [Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1993-94, R.S.]. The magical landscape of Paradise was shown in all its glory and below it, as its antithesis, were placed 50 million and 180 million year old fossils, animal skeletons, and bottles from the Old City of Jerusalem containing holy water, oil, and earth. From the labels I erased the word “The”, and thus, for the first time, still in an unconscious manner, I inserted a critical and unsettling element into the concept “Holy Land”. The early Paradise blended with the image of the Holy Land and exploded in its conflict with current reality.” Littman-Cohen began to create series of “products” from the Holy Land, as for industrial-commercial production: air, water, earth (Holy Land for Sale, 1996; Holy Air for Sale, 1996; Holy Water, 1998). These works were created with an awareness of the connection to the popular manufacture of bottles containing “Holy” earth, water and oil which are sold in Christian holy places, especially in Jerusalem’s Old City, as “authentic” souvenirs from the Holy Land. This action joins the artist’s stated strategy from the start of her work: collaboration with private and state companies, in order to point out the place of the consumer in the post-materialist

age [3].

With White Land, 2001 Littman's work becomes outspokenly political. The artist makes use of photographs that map the entire country, where large areas have been erased at the order of the Military Censor. The use of photographs as ready-mades emphasizes the actions of erasure, concealment, and camouflage to reveal information, that the establishment has tried to reduce and hide from the public. By the referencing of conceptual actions on the white stains Littman-Cohen upturns the purpose of the authorities concealment. The lacking and disappeared become exposed and concrete, building a new reality for Holy Land, a type of virtual-territorial sieve: Hole’s Land [4]. The “White Holes” are not the artist’s initiative, as in the works of the artists Meir Gal and Eti Yakobi, but were “imported” from the Israeli public sphere that is subjected to the outlook of the military establishment. As with Hans Haacke, who since the 1970s reveals the apparatus and veracity hidden behind seemingly innocent state institutions, Littman-Cohen reveals through the white stains the Establishment’s continuing and purposeful activity, which misleads the innocent individual, and also tries to subjugate the civil administration to the military one, a trend which has continually gained strength since the summer of 1967. The white stains, the action of erasure and the action of concealment, the innocent forest ravaged at the hands of the army – all these are but a few visual symptoms of the phenomenon, actualized in a tangible manner. | | | | 1967 | | | The Six Day War: the “Great Victory”, euphoria, national elation, self-contentedness amongst the Israeli public. The quick victory was seen on many levels of Israeli society as the high-point of realizing the Zionist dream. Just a few understood that the glowing triumph and conquered territories would bitterly lead to difficult consequences, bad fortune. The official Israeli explanation wanted to emphasize the view that the country was in a state of continual preventative war, and only the strength of the army could secure the Jewish sovereign existence in the area; the political and military system continually proclaimed messages of the need to increase security and acted to found and increase the army’s power and scope. The Jewish communities in the Diaspora enlisted to support the State of Israel, mainly through the raising of funds and donations. The security of the State and the army was obviously placed at the head of national priorities, and enjoyed great ideological promotion in comparison to any other issue – social, civilian, etc.. New forms of Israeli identity, based on militarist concepts replaced, or distorted, previous values and images that had became seemingly out-dated, such as the figure of the pioneer, that symbolized the basic concept of the “old” Zionism [5]. The importance and power of the military establishment grew, and the civilian society was willing to accept this, at least during the years immediately following 1967, as a necessity. Even though other voices started to be heard and fissures started to appear in the hegemonic concept from the late 1960s onwards, its residue exists to this day.

The white stains, “threatening stains”, in Littman’s words, and the trees used by the security establishment – land requisition, planting for camouflage, for security purposes, or alternatively, uprooting for security purposes – are used by her to make a pointed statement: this is a vulgar habit, of the military establishment penetrating the boundary of the private and the public.

Littman goes along the trail of Paradise Lost [6]. She states, for example, that when she first traveled to the memorial site of her grandfather (in 1992), a mythological figure from her childhood, there was a sense of magic in the air. It was a winter day, the pastoral area was immersed in peace and quiet, birds chirped, and from the earth rose that intoxicating smell it gives off after rain. On arriving at the site the first warning light was lit. A cautionary sign: “no photography allowed,” and the people from the JNF forbidding her to enter and see the memorial plaque donated in memory of her grandfather. She insisted, and from the moment she tried to enter the forest it changed its skin: The good forest, relaxing, pacifying became the threatening forest, concealing, hiding (Gerald Durrell’s The Drunken Forest becomes the Haunted Grove of William Shakespeare’s, A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream.) It was like the expulsion from the magical and holy Paradise, from the entranced primordial forest. The peaceful nature became one of danger and mystery (Casper David Friedrich), and cultural associations in the collective awareness were planted. Or in Nissim Aloni’s words: “In the head are pretty pictures of an organized human landscape, but in the stomach is a forest, the old forest, the forest that is never erased…” (from The Gypsies of Jaffa). As in Aloni’s plays, Littman-Cohen also tries to erase the old forest in the stomach, but it chases her, and doesn’t let go, and she returns to deal with it in an obsessive manner, onto an unclear point on the horizon [7]. In Jungian teachings the forest symbolizes the unconscious and powers of danger and intimidation. In European folklore and fairy tales the forest is place of mystery and danger, of the unknown and uncontrollable. Desires and dreams on the one hand, threatening, uncontrollable and invasive powers on the other, it all whispers in Littman-Cohen’s “in the stomach, in the forest” potion. The forest as backdrop, the forest as camouflage, the mysterious forest and the “haunted grove,” the forest embodying great powers, the Paradise Lost of Littman and of Israeli society.

In the European tradition, finding a path in the forest emphatically symbolizes the acquiring of knowledge of the adult world or of the self. Littman tried to hold on, for just a moment, onto the religious myth of the Holy Land, as it was constructed in her childhood awareness in the Catholic school (as in Paradise Lost, which was written through religious experience.) This happens first in the magical forest of childhood, and later, in adulthood through sober and intellectual walking along the forest’s paths. She aimed to build a personal yet also collective map of the country, but was again expelled from her personal Paradise. For Littman this is the Holy Land in its contemporary form. | | | | Notes | | | 1. The action, at first done intuitively, expressed anger, and only later did Littman-Cohen see it as an act of protest. From conversations with the artist, December 2000 – January 2001.

The following notes are from the same conversations with the artist.

2. According to Littman-Cohen, this was reminiscent of her action at the Bograshov Gallery, 1992: the placing of botanical signs without plants.

3. The companies and bodies Littman-Cohen has collaborated with are: Jewish National Fund; Arim, Urban Development Co.; Eden Springs, natural mineral water; Materna; Air Monitor Ltd.; and Panorama – Imaging Technology.

4. In this context Mona Hatoum’s work Present Tense, 1996 should be mentioned. It was shown at the Anadiel Gallery, Jerusalem: a map of the Oslo Agreement, assembled from small olive-oil soaps from Nablus and tiny red glass beads. The work showed the Palestinian “threat” that will be created in Israeli territory, and the segmentation of the Palestinian territory, as suggested by the Oslo Agreement. Littman-Cohen’s White Land, as with Hatoum’s work, points out the isolation, paralysis of and the control over geographical areas by the Israeli military and establishment. See: “Interview; Michael Archer in Conversation with Mona Hatoum,” in Mona Hatoum (London:Phaidon,) 1997, pp. 26–27.

5. See S.N. Eisenstadt, The Transformation of Israel Society, (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, The Hebrew University), 1985.

6. Paradise Lost, by the prosaic English poet, John Milton, was written in the years 1658–65. Amongst other things, the work describes the expulsion from Paradise.

7. For this reason the artist wished in 1997, out of a emotional and intuitive decision, to replace the memorial plaque from its imprisonment by the military powers in the threatening, “Forbidden Forest” to an area of “domesticated nature,” designated for leisure and relaxation.

Translated from the Hebrew by Timna Seligman | | |

| | | | See the Artist web site | | |

| | | |  | | David & Gisele Littman, 1967 | | |  | | Ariane Littman, The first action, 1992 | | |  | | Ariane Littman, Mobile Forest 09 | | |  | | Ariane Littman, Mobile Forest 06 | | |  | | Ariane Littman, Mobile Forest 08 | | |  | | Ariane Littman, Mobile Forest 04 | | |  | | Ariane Littman, Mobile Forest 02 | | |  | | Ariane Littman, Mobile Forest 07 | | |  | | Ariane Littman, Mobile Forest 10 | | |  | | Ariane Littma Mobile Forest 11 | | |

|

|

| |

|

|

|