| Exhibition catalogue: | | | | 1. Abigail Solomon-Godeau, "Living with Contradictions - Critical Practices in the Age of Supply-Side Aesthetics". The essay was originally published in: The Critical Image: Essays on Contemporary Photography (Carol Squiers, ed.), Bay Press, 1990 | | | | 2. Rona Sela: "When Values Become Forms - When Forms Become Values" | | | For the first time, both the exhibition and the catalogue focus on non-modernist trends in the sphere of local photography from the 1970s to the beginning of the 1990s. They deal with the evolution of photographic practices in Israel during these years, and seek to differentiate between local modern photography, which enjoyed a canonical status in this country until the late eighties, and photography that is based on non-modernist paradigms. This trend in photography was considered esoteric for many years – only recently emerging from its marginal position – and its importance as a medium for representing our contemporary experience of life has been accorded growing local recognition.

The exhibition and catalogue outline several turning points of a distinctly local character that have determined the course of photography’s development in Israel over these twenty years. Reflection upon these processes - the tentative conclusions which were first presented by me in The Range of Realism exhibition (Tel Aviv Museum of Art, September 2003) - may provide a new perspective for illuminating contemporary photography. This should be based both on the transformations that the local map has undergone during this period, and the international art discourse and its impact on that map (Post-modrnism, gender, etc). | | | | Before I turn to contemporary photography in Israel, I would like to note that for more than a decade the focus in the international art discourse has been on photography, its capacities, the representations it engenders, and the philosophy that underlies it. Hence, it is no longer possible to divorce photography from the art discourse in general, and to discuss it as an independent entity (e.g., by theorizing “photographic art/[fine-] art photography” or “postmodernist photography,” or by plundering the realm of photography and appropriating its “star of the hour,” who uses photography as a main instrument, for the sphere of art). Any concrete value focused discussion of the status of photography will undermine such an endeavor. The importance of the exhibition and the catalogue lie, therefore, in its proposed historical revision or insight and in its remapping of the photographic terrain. | | | | The Seventies – From Tool of the Margins to Tool of the Center | | | The “beginnings of Israeli photography” are commonly situated in the late seventies. This period was marked by the return to Israel (mainly from New York) of a number of artists – “The Desert Generation” [1] – who had specialized abroad in photography and who would demonstrate a prominent institutional presence in the years to come [2].

In this exhibition I would like to propose an alternative historical view. In my view, the essential turning - point with regard to photography occurred at an earlier stage – towards the mid-seventies, when conceptual artists began using photography as a tool in their own work. In contrast to the dominant approach, my reading does not accord esoteric place to what was done here in the field of photography until the seventies [3], but seeks to point to a potential shift that the seventies offered on an invisible level. In her essay for the first exhibition of the Israeli Photography Biennale catalogue, Galia Bar Or writes: “At the same time (concurrently with the consciousness of the practical applications of photography, R.S.), there began the use of photography in artistic contexts, in the service of printmaking and of conceptual art…But in the wake of these trends, during the seventies there arose an awareness…which was accelerated by the involvement of graduates of photography schools in the United States in art photography activities in Israel” [4]. i.e., Bar Or mentions conceptual art only as a first – but esoteric – manifestation, and as a background to the activity of the photographers, who returning from New York with newly acquired awareness, were to establish “the art of photography” in this country. Contrary to this view, I wish to designate the conceptual art of the mid- and late seventies as an area of import also in distinctive relation to photography, a relation thus far ignored by local theory. In this charged and intense sphere of activity there was, as we shall see, a concealed potential for a change of approach towards photography and for the emergence of a critical postmodernist photography in the wake of Pop Art and Conceptual Art. But certain power relationships and unique historical circumstances prevented the realization of this possibility in Israel.

The conceptualist seventies could be divided roughly into two main orientations, and in the discourse of both the camera served as a major tool. The first orientation – the “pure” conceptual reductive one – championed the effacement of the object in the name of the idea (every component was conceived as an action and as a concept), and its roots can be found in international Minimalism. This formalistic, cold, almost scientific approach is identified in Israel with “the Jerusalem artists” [5]. As part of this orientation one can point to the actions performed by certain artists (e.g. Pinchas Cohen Gan, Avital Geva, Dov Orner, Micha Ullman etc.) at specific sites (the kibbutz, the border, the Occupied Territories, etc.). These local/political/social actions placed themselves concretely and conceptually away from the center – at the margins. The distance from the center also found formal expression through the rejection of the artistic object, the elimination of the artistic surface, and the rebellion against the convention of exhibition at art galleries or museums and other institutionalized spaces. Paradoxically, the human aspiration to document transient and passing events such as these (as testimony of their actuality, and for the sake of historical preservation) restored them to a state of concrete material. For in their need for the mediation of the camera to reproduce their work in the public consciousness (“the act of courtship”), these artists set anew the borders of artistic activity that they had tried to demolish with a practice that had transformed the body of the artist or a specific site into the act of art per se. The camera revealed the paradox that stemmed from this practice: the photograph as the sole lasting document, i.e., the “object” of those actions. Spirit has become matter once more [6]. The act of the camera (in documentation) – being a marginalized act – reversed the initial intention, and thereby became a subversive, albeit central, tool in the discussion of these activities. Needless to say, these works ultimately found their place within the walls of the museum, which by definition is designed to preserve art of all generations. So here we have yet another distortion of the initial intention. On the other hand, in this way photography became part and parcel of anti-object art – one of the avant-garde art currents of those years. On this occasion, one may note, the modernist approach to photography was challenged for the first time in this country.

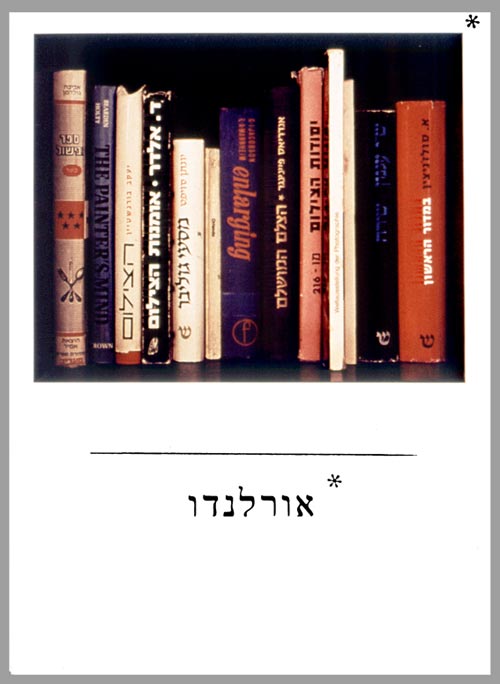

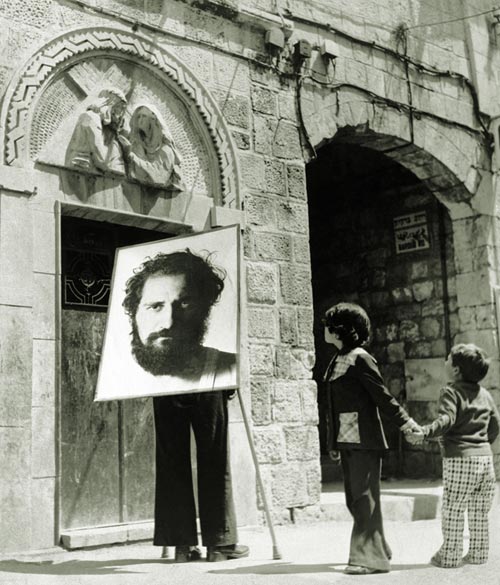

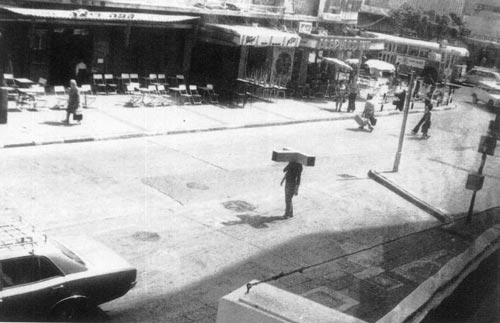

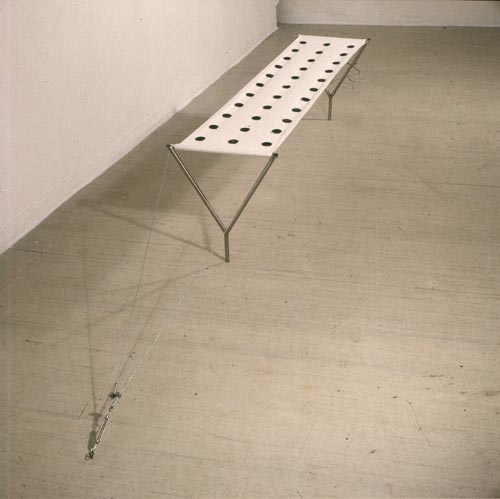

The other orientation, “ Conceptual Stylism” [7], was represented in Tel Aviv by the Midrasha (the Art Teachers Training College, Ramat Hasharon) school, and was associated with the tradition of painting (in opposition to the purist conceptual orientation described above, which rejected this tradition). Over the years, this orientation became canonical (a process marked only in 1986, in the Want of Matter exhibition), i.e., it was embraced by the center. Its beginnings, however, may be designated by the “naturalization” of Pop Art in Israel [8], embodied, inter alia, in the incorporation of everyday consumer products in artworks, and in the production of series and multiples. In this context a major role was accorded to photographs. Among these were photographs from newspapers and magazines, iconic photographs of “culture heroes” (e.g., pictures of political or military figures, such as Itzhak Navon [a photograph distributed as a gift to readers of the Yediot Ahronot daily], Willy Brandt and David Elazar, which Raffi Lavie inserted in his works), advertisements and photographs of mass consumption products (postcards, photographs from the TV screen, etc.). The visual result generally had the texture of a collage, which brought together photographs, plywood, drawing and text. Raffi Lavie was the spiritual mentor of this school, which included Yair Garbuz, Michal Na’aman and others. Later on, photography was channeled to additional directions, and not only by graduates of the Midrasha [9]: documentation of performances (Efrat Natan); factual, cold, almost scientific use of photography (Dganit Berest, Orlando, 1975; Michael Druks, Medium-Medium, 1974); conceptualist use of photographic material to stratify the information imparted (Michal Na’aman, Blue Retouching, 1974) [10]; Photographs as by-products of the wave of “Earth Art” (unlike the “Jerusalem artists,” who conceived the action itself at a specific site as an act of art, which assumed a political, subversive, and anti-Establishment value, here the artists treated the landscape as a material surface; politically, in the case of Michael Druks [Maintenance Work, 1977] and Michal Na’aman [The Eyes of the Country, 1974], for example, or apolitically as in the case of Yossie Asher [Water Lines, 1979 - 1980 – drawing with string and water in the landscape]); innovative use of the body, influenced by Happenings, Body Art, and performances which were staged elsewhere in the world (Yehudit Levy, Airplane, 1974 – an act ranging from performance to immortalization by means of photography; Haim Maor – drawing on a body with black adhesive tapes and documentation consistent with photographic values [11]; Moti Mizrachi, Facing the Town, 1974 – a work that becomes a sculptural monument [an installation] in the space due to the visual power with which it is invested by the photograph); forced accommodation of conventional photographic portraiture to avant-garde requirements (Yehudit Levin, Really and Truly, 1975 – a collage, without a plywood surface, that uses the “tradition” of self-portrait photographs as an act of revelation and exposure; Dganit Berest, Ruthie is Photogenic, 1977 – cold and quasi-traditional “scientific” posings, almost like those familiar to us from the automatic passport-photographs, which aim at exposing the falseness of the portrait photograph; Michal Na’aman Blue Retouching [12]), and others. By adopting photography as a tool that contests the artistic framework, these artists felt liberated from the need to adhere to its technical capacities. Hence, most of the works are devoid of the technological mannerisms of photography, consecrated by modernist critical practices – “correct photography,” “the appropriate print,” ”the decisive moment,” “the chosen frame.” etc. Instead, they challenge the sanctity of these imperatives by means of an almost deliberate incorrect employment (“bad photography”) of those very same mannerisms. In this respect, the argument raised by “art photographers” against Lavie’s alleged alienated approach to photography [13] seems somewhat contradictory: while still using modernist practices of photography, these artists were striving to join in the local, critical and value-laden art discourse, an aspiration incompatible, as we have seen, with the modernist conception of photography. At any rate, the initial use of photography by conceptual artists as “a marginalized tool” [14] offered them alternative artistic purviews with respect to the conventional media consecrated by the art establishment. The use of photography thus came to be perceived as oppositional, as a “rebellion” against the art establishment and its conventions, and became part of the avant-garde wave of the seventies. The “guilty presence’ of photography, which is also reflected in the material, served as a fertile soil for those artists who had not abandoned the artistic object. This device also enabled them to constitute a discourse beyond the formalistic confines of photography and to raise questions of meaning and context (a possibility that would be realized later in American postmodernist photography) in relation to the linguistic signifiers that were prominent in their works [15]. The Gospel According to the Bird, 1977, Michal N’aman’s enigmatic, sarcastic, and provocative work, is a fine example of the mobilization of the “low” character of photography for subversive and critical purposes. By pasting together fragmented photographs of animals, the artist produced an image of a monster, a kind of parody on our impossible hybrid union with the West. In Na’man’s opinion, photography, an off-center tool at that time, allowed what painting did not: the creation of an image [16]. This approach, which exploits the exclusion and the “inferiority” of photography vis-à-vis other “ high” arts, was about to have parallel applications – as we shall see – first abroad and then in Israel. | | | | From the Seventies to the Eighties – Modernism Revisited | | | Towards the end of the seventies, most artists abandoned the photographic practices and reverted to painting. Looking at this period, the first explanation that comes to mind relates to the worldwide wave of a return to painting, a move that was acknowledged and legitimized by the local establishment in the exhibitions A Turning Point 1981, and Here and Now, 1982 [17]. In my conversations with various artists, the issue was raised, and their explanations of this phenomenon have been diverse, and primarily personal [18]. In any case, the artists’ abandonment of photography, on the one hand, and the adherence of the photographers to the modernist code (which I will discuss below) on the other hand, relegated photography in Israel to a state of regression. The move described above – the co-opting of photography into the mainstream of the art-world through the utilization of the camera for new objectives in the service of the avant-garde art of the seventies – echoed practices from the international scene: documentation of performances, Body Art, temporary installations, outdoor sculpture and projects of Earth Art. In Europe, and especially in America, the anti-Establishment approach of Conceptual Art (and the spirit of collage and Pop Art that mediated between the self, the society and the time), were kept alive by artists like Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Barbara Kruger, John Baldessari and Sherrie Levine (the first generation of artists to use postmodernist practices in photography). These artists started diverting the formalistic course of the history of photography by rejecting its most esteemed conventions: sanctity of the photographic paper and the camera and the right exposure and print. * This shift was consistent with the by-products of the conceptualist actions, which deliberately ignored the formalistic features of photography (in contrast to the modernist photographers’ veneration of these features, according to which they also defined themselves) or deliberately used its properties in a defective manner, as part of a tendency that contested the aesthetic, the conservative, the establishment-approved, the object).Conceiving photography as an “other” (i.e., a “low” medium with respect to “high” art) was well suited to a discourse that sought to break the repressed silence of social “others,” i.e., of minorities and underprivileged groups. In her essay on Cindy Sherman, Lisa Phillips speaks about Sherman’s precise and interested choice of photography: “ To Sherman, the secondary status of photography in the art-world forms a perfect corollary to the status of women in a patriarchal society, and she uses each situation to question our assumptions of the other [19].

In this context, it is also worth mentioning the work of Israeli artists Naomi Talisman and Adi Ness from 1993 [20]. Talisman and Ness set out to document the homosexual and lesbian community in England. Beyond the political aspects that their work represents, the immanent, non-patriarchal and non-ethnocentric stand that they take points to the moral delusion embodied in the external representation of “other “groups (the exploitation of groups that are discriminated against for the advancement of one’s own interests). Hence the fact that the work is produced from the inside, as an integral part of, and from within the group they are discussing, is of major importance. Through the “other.” Ness and Talisman, like Sherman or Lorna Simpson, define their own position, a position that is struggling for recognition. At any rate, these practices expropriated photography from its conservative uses and shifted it to a more public space. In their works, these artists, along with John Baldessari, Victor Burgin, Bernhard and Hilla Becher, and Dan Graham, and young artists like Louise Lawler and Laurie Simmons (of the “second generation” of photographic postmodernism), have all marked out their resistance to formal analysis and to their positioning within the modernist paradigm. This was not a rejection of Conceptualism but a new way of according value to images, considered as raw material that presented a non-hierarchical hybridization of presented contents – an act which marked the beginnings of the postmodernist preoccupation with photography.

In Israel, in the early eighties, things developed differently: only a few of the conceptual artists continued using photographic practices as an integral part of their work and concurrently with their painting or sculpting activities. Likewise, towards the end of the seventies as mentioned, photographers who had studied abroad (mainly in New York) returned to the country. These artists, also dubbed as the “New Photographers” [22], did not relate to local materials and to contemporary cultural practice (which was breaking the ground for an art with a different character) or to the budding global postmodernism, but adopted the values of non-experimental modernist photography in the vein of Arthur Freed, Phillip Perkis, Robert Frank, etc [23]. Thus almost the only photographic work, by definition, done in Israel until the mid-eighties encoded itself as “art photography,” in line with the distinction provided by Abigail Solomon-Godeau [24]. Hence the span of years between the end of the seventies and the mid-eighties in Israeli photography can be designated as re-modernism, or as a reversion to modernistic idealism.

Until the return of the “New Photographers,” an uninterrupted tradition of direct, purist photography, conscious of modernist aesthetic aspects, prevailed in this country [25]. This field was subdivided functionally into press photography (from Boris Carmi, through Micha Bar-Am to Shlomo Arad), social photography (e.g., Yoram Lehman in Yeruham [1978]) and landscape photography (like that of Peter Merom’s The Song of the Dying Lake, 1960, or that of Drora Spitz, Chanan Laskin, and David Maestro), or experimental landscape photography, (such as that of Dalia Amotz). Returning from their studies abroad, the young generation of photographers emphasized the personal and the experiential (in non-documentary photography that did not abide by the tradition of nature photography) instead of the political and the critical. In his essay for the Beyond the Frame exhibition, Yehoshua Glotman claims that the young artists working in Israel in the early seventies had to grapple with a tradition of photography that dealt with reality in a direct manner, as “engaged photography,” i.e., photography in the service of “noble ideas”: “They considered relating to reality an anachronism. Their need to go out into the street and discover life had almost vanished. For this reason they sought ways in which they could express their personality in a different and original way” [26]. This fact along with the struggle for the legitimization of photography, Glotman argues, led these artists to emphasize and bolster the personal in their work. Hence, he presumes, one of the frequent means was reverting to photography in the “family territory” or returning to the regions of childhood in search of one’s roots (Simcha Sherman – Acre, for instance), and he adds: “Photographers such as Avi Ganor, Boaz Tal, Oded Yedaya and others focused on what went on within the family, a preoccupation that ‘exempted’ them from the burden of grappling with the external reality, with all its social and national weight…” [27]. Other factors, too, however contributed to the shaping of the local scene: the inauguration of separate photography departments in the various schools [28], the establishment of separate museum departments of photography, in the spirit of John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art, New York [29], and the opening of galleries specializing in photography [30]. Prima Facie, Israel was having a photographic boom, which also manifested in the abundance of activities described above. In retrospect, however, it appears that this activity (the summation of which found expression at the first photography biennale held at Ein Harod in 1986) signaled a wave of revival of modernistic values. Once more the agenda included themes like subjectivity and originality, restoration of the auratic image, aesthetic idealism and a formal, non-ethical judgment of the artwork (within an autonomous framework), namely: a reading that does not propose critical and analytical investigation on the representational or institutional level. The pure aesthetic tools of the “New Photographers” (tools that were contested by postmodernism) left them outside the international art discourse. When the world marked the shift in art theory from presentation to representation, the canonization of modernist photography could be maintained (and justly so) only from a defensive position. Furthermore, the self-imposed “ghetto,” co-produced by these photographers and the Establishment, contributed considerably to the hierarchical division and categorization [31], to which the seventies had offered an invisible alternative that was never realized at the time. | | | From the Mid-Eighties Onwards

The Beginnings of Postmodernism in Israeli Photography | | | In Israel it was only around the mid-eighties that there appeared expressions (albeit still inarticulate culturally) of postmodernist practices in photography, in its capacity as an agent of transmission of cultural and ideological changes. It should be noted that the postmodernist “actions” could not cohere into a school or style of any kind (this would have been contrary to the essence of postmodernism), their primary intention being the discovery of a wide range of multifarious interpretations and concerns within the photographic context. What united all these practices and interpretations, was their opposition to the formal analysis or to the upholding of the modernist model. “A formulation of common critical ground [which] would encompass a shared propensity to contest notions of subjectivity, originality, and […] authorship” is how Solomon-Godeau defines it, and she continues: “Such work specifically addresses the conditions of commodification and fetishization […]. The purviews of such practices are the realm of discursivity, ideology and representation, cultural and historic specificity, meaning and context, language and [linguistic] signification” [32]. In her view, it is inevitable that photography should be essential to the postmodernist discourse, since every critical or theoretical issue concerning postmodernist art is traceable in photography. Issues relating to authorship, subjectivity, and uniqueness are structured in the very essence of photography, while issues concerning simulation, stereotypes and the sexual and social attitude of the viewing subject play a central role in mass media photography. Seriality, repetition, appropriation, intertextuality, simulation and pastiche are the principal devices used by postmodernist artists to repudiate the putative autonomy of the artwork as conceived in modernist aesthetics, and to construct a new meaning for the signified and its object of reference. Hence concepts such as intention, representation and context take on a special importance in the postmodernist discourse [33]. On the more general level, this approach conceives of photography as a device, the conscious use of which is designed to exploit to the maximum its capacity to reflect the essence of life in the postmodern era. This approach advocates a multiplicity of modes of representation in the individual work, and a stratification of its meanings. Hence, its non-hierarchical and non-centralistic (there is no dictating center) practices and values are pluralism, complexity, diversity, eclecticism, appropriation and quotation from mass media and other fields of activity that deal with the materialistic and the sensual (materialism versus the idealism of modernism), discuss the represented and the virtual, touch the non-aesthetic and the amoral, return to the local with an emphasis on the personal, the non-ideological, the non-revolutionary, the representative of the “other,” etc. In opposition to the canonical approach (“photographic art/art photography”), the postmodernist approach is derived from the essence of photography and its products in the present. In Israel, as aforementioned, towards the mid-eighties one may discern some signs, on one level or another, of a postmodernist approach in photography. Its presence begins to be marked in the works of various artists. The first wave consists of Moshe Ninio (in an exhibition entitled The Silver Era, Givon Gallery,Tel Aviv 1983 – among the first exhibitions to deal with deconstruction, the dissolution of the image by photographic means, counter-photographic photography); Dganit Berest (in The Discussion exhibition, Julie M.Gallery, Tel Aviv, 1983 – an exhibition that was devoted to a series of works produced by Berest after a photograph of a group of New York artists discussing problems of narrative art); Michael Rohrberger (who displayed modified “ready-made” photographs found in the street at the Sara Levy Gallery in 1981 [the first in this series of exhibitions was held at the White Gallery in 1978] [34]); Boaz Tal (who in the mid-eighties moved from family photography per se to that which appropriates art history icons); Oded Yedaya (who proceeded from the practice of “pure” family photographs that he had adopted in the late seventies to introducing decorative and disruptive texts in the surface of the photograph); Ronit Shani (who moved from direct street photography in the mid-seventies to the production of postmodernist works after studying in New York [1983-1985]);Yehoshua Glotman (who dealt syntactically with local, anthropological motifs. Derived from the co-existence, side by side, of various cultures [like culture of the “other”], while emphasizing the personal and as a follow-up of his early eighties Israeli Album).

The second wave includes artists such as Michal Na’aman (newspaper pages as the base of works – Photographer Unknown, Sorting); Bareket Ben-Yaakov (eclecticism, gesturing, quotation, blatant coloring); Roi Kuper (libidousness, expressiveness, mysticism, strongly inspired by European artists who deal with issues of memory); Gilad Ophir (deconstruction of the “significant form” and the presentation of its transformations, as, for example in the work Mark-Structure, 1990-1991) and others. In this context it is worth recalling the practice of appropriative photography, i.e., photography produced after, and in homage to other artists, reflecting a historicist vision. An echo of this practice with its various manifestations is found in the works of artists such as Ronit Shani (The Thing Itself No.1, 1985 – a work produced during her studies in New York, after Edward Weston’s Peppers, and hence also after Sherrie Levine’s works after Walker Evans and Edward Weston); Sigal Primor (works after Marcel Duchamp and Alfred Hitchcock); Boaz Tal (Pieta No. 9, Homage to Eugene Smith, 1990 – a work epitomizing the shift in his work); or in the works conversing with local artists and with Israeli history, like Arnon Ben-David’s For Sale: Helmar Lerski Photographs 1935, 1991 or Aïm Lusky’s We are all the National Guard - Post Semiotic Work No 11 (the latter is based on pages from a government documentary book about Eretz-israel issued in the fifties, and reconstructs the history of viewing from a historical perspective); or in the works of Yitzhak Livneh (Love, Peace and Security, 1982 – a work created during Livneh’s stay in the United States, and was probably produced at the same time as Richard Prince’s advertisement icons [Marlboro Man]), Michal Heiman, Dan Zakhem (postcards, works printed on “The Back Page” of the Local Tel Aviv weekly Ha’ir etc.) and others. In contrast to other places and especially the United States, in Israel the shift in the value-focused conception of photography began among artists from the realm of photography [35]. These artists wished to rebel against the canonical photography and the pure aesthetic codes that were of its essence, and to expose values that would make it possible to constitute a discourse of a new kind. Concurrently, the eighties have witnessed the opening of a large number of interdisciplinary and alternative galleries, which offered a possibility to develop a counter-line to the one represented by the Establishment [36]. | | | | The Nineties – Towards a Material Post-Conceptualism | | | The young artists active today in the photographic terrain in Israel articulate in their works a changed cultural reality, a reality that the Establishment can no longer ignore. However, they owe the breakthrough to the group that has been active here since the mid-eighties.

It is interesting to note that contemporary artists also engage in a dialogue with works produced here in the seventies. Now, as then, photography is consciously political. But the image of society, as it was reflected (on the ideological, political level) in the works of the conceptual artists is absent from the works of contemporary artists. For them, the “self” has shifted to the center of attention, and the discussion of social topics focuses on aspects of particular interests like power, sex and gender, out of concern for the welfare of the individual rather than of the society at large. Ideological considerations have made way for group or individual specific interests. As part of this change, direct and political photography has attained recognition and enjoys legitimacy as an art form. Generally speaking, this move is more marked in American practice than in European [37], and is evident, among other things, in the scope of attention devoted to topics like the position of minorities. On this background, I would like to indicate several elements common to contemporary Israeli artists and the conceptual art of the seventies, and to examine the new values they add to in their work. In my view, the work of Tiranit Barzilay, the most political and socially involved among the young artists active today, is an appropriate point of departure for a critical comparison of this kind [38]. Barzilay’s scene of activity is tangent to that of Efrat Natan in the following instances: in the work Milk, 1974, the site of Natan’s activity is a typical Israeli apartment-house stairwell; Barzilay’s site of activity in Untitled, 1993, is a shelter (a distinctively Israeli, public air-raid shelter). Both make use of white materials (Barzilay cleanses the scenery she sets up from color images and introduces a lot of white signs into the color photograph, which ends up looking almost like a black-and-white print): a flag, milk, Memorial Day white shirts, which are also items with a social-symbolic significance. In the work of both artists, the staging or the theatrical act (the set construction) is a central motif. Both demonstrate an economic and precise choice of images with the intention of controlling the message communicated to the viewer. But whereas Natan performed her actions in the seventies qua final acts and then documented them, which made the photograph a “necessary overlapping excess” as far as she was concerned [39]. Tiranit Barzilay today “builds” actions in order to photograph them (the photograph is the ultimate aim and product). Barzilay uses the technical properties of photography in order to go out into a more public space and discuss the phenomenon of a certain social stratum (“Sheinkinaim” [“Sheinkin Street people”], twenty-year olds, who project fashion-consciousness, self-awareness, and an affinity to the world of advertising and copywriting). Although the theatrical act is staged for the sake of the photograph, the photograph accords the work a kind of documentary validity. In Michael Druk’s work Medium-Medium, 1974 (medium meaning a means of expression or creation, in this case: photography, cinema, painting; and medium in the sense of an intermediate size of measurement) the semiotic ambiguity indicates ambivalence: the essentialist discourse overlaps the formalistic discourse. The cold, almost devoid of any aesthetic value, photograph uses a strategy of reproduction. The same act of semiotic delusion, which rests on visible formalistic frameworks, is to be found in the works of Yossie Breger’s, Entrance, Rewind, and Untitledv, all from 1994 (where does the viewer stand? which is the interior and which the exterior? The visible inversion of the text parallels the inversion of meaning) and in Ram Bracha’s Art: Pricing Methods (proposal no. 1) , 1994. The use that both artists make of the photograph as a reproduction, and their mock presumption that it is possible to set a logical construct that implies a certain order for examining things, are refuted by the internal syntax of the works. In Art: Pricing Methods (proposal no. 1) , Bracha marks the “order” of things through an illusionary method for evaluating artworks (as the title of the work ostensibly promises), while in the background remain unremitted questions: is a print (a reproduction) priced at one dollar more valuable than a print priced at a hundred dollars? Who determines their real value in the market? According to what criteria? The inversion of the intention becomes visible. The attempt to constitute a method of this kind is once more refuted as one listens to the monotonous soundtrack that accompanies the work. In the works, Entrance, Rewind, and Untitled, Breger refers to at least two worlds, or more precisely, proposes two primary vantage points for grappling with the given, the factual, the existent, whereas the closed door, fixed in a given position in such a way that it will never open, “opens” a third possibility, etc. In these cases, the attempt to read the work of these artists on the conceptual-verbal level only (as though it is enough to describe the work as an idea, and its realization in material is virtually redundant) is revealed as impossible. The material has a value import of a central protagonist in the game of deception and the power relationships created between the viewer and the work.

In this vein Nurit David writes in the text accompanying her work The Photograph (1) , 1991: “ The photograph carved the name of the family tie in the rock. The technique enables concealment of the connections, like the unhewn back of the girl that is connected directly to the mass of rock, and the connections between the figures in the place where the girl’s arm touches the woman’s shoulder, and in the region of the knees [40].” In Orlando, 1975 (a “neutral” seemingly devoid of aesthetic values, photograph, which recalls a “scientific” photograph of any shelf of books), Dganit Berest has isolated, supposedly arbitrarily, a single book (marked with an asterisk) from a row of books that might be found in the living room of an average person. In another of her works, The Circle by Virginia, 1976, under the re-photographed reproduction of a portrait of Virginia Woolf there appears an apparently “neutral” text that characterizes her in the following manner: “Virginia Woolf, a fascinating and unique English author, and one of the important innovators in the sphere of the modern novel.” The isolation of one random object or a characterization that is actually devoid of content that does not provide us with any real new information) emphasizes, on the one hand, the absurdity (who is inside? who is outside?) and the social banality that is reproduced in society salons and, on the other hand, the concealed intention of reversing the repetitive code of reading. Here too the resort to language as a subversive act, the reversal of intentions (Push, Entrance) and the use of photography in the reproduction form (“pure” uninvolved photography, free of values other than those of the documentation itself) and of material and functional objects/images for purposes of social and value-oriented statement, create an intricate network of meanings. In these cases a photograph without text is like an empty sign, unclarified and meaningless. In this context, it is worth recalling the distinction made by Rosalind Krauss, who showed how photographic “snapshots” are used as ”Readymades,” which remove an object from the continuum of reality, according it the permanence of an artwork by means of choice, isolation and consolidation [41].

The text accompanying the photographs (like picture captions in a newspaper) is conceived as necessary for complementing the empty sign with meaning (in correlation not unlike that of an index and a text). In this context, Tamar Getter’s work A letter to Beuys, 1974, comes to mind. In this work, which is addressed to the German conceptual artist, Getter made use of both the ambiguity of the text and the photograph, i.e., the medium, in order to arrive at multiple perspectives for examining reality. Getter outlined a story that undermines the possibilities of simplification and of essentialism. The letter consists of three different testimonies (Japan, Moscow, Israel), while the photographed image is single. The multiple points of view paved the way for a discussion on the themes of truth and fiction and demolished the hierarchical value preferences of one over the other. In this case the text exacerbated the difficulty of reading the representation in a unified manner. The artists of today use this tactic, but they hone it. They “lure” the viewers into an ostensibly innocent set, in which they are subsequently trapped without an easy way out. At first sight, if one opens the door or listens to the soundtrack, the order of things becomes comprehensible. But the moment that has been done, one finds oneself in front of infinite reflections or choices, which underscores the impossibility of finding the sole “real” representation of a homogeneous set of signs. Druks, on one side, and Getter and Berest from another direction, tried to upset the autonomous boundaries of art and to propose in their stead a heroic unity with life itself. The works of Bracha and Breger, in contrast, depict the reality from an external point of view. Although they criticize it (Bracha’s criticism of the power relationships that govern the art establishment, for example, is political [almost Marxist], exposing “the tyranny of the signifier, the violence of its laws,” [42]), they do it by means of a sterile use of objects that represent concrete mechanisms. Vaniah (Vajezatha) , 1975, by Michal Na’aman, a work that juxtaposes the phallic with the vaginal (metaphorically: a fish with a bird); Tamara Masel’s feminist work from 1993-1994; the man and the woman, Adam and Eve in Untitled, 1975-1976, by Haim Maor, along with Man and Woman, 1988, by Gilad Ophir (a work comprised of images appropriated from the TV screen, which discusses gender representation by the media); Stitched Face, 1974, by Yocheved Weinfeld; Blue Retouching, 1974, by Michal Na’aman; and body parts in masochistic droppings and on impossible formats by Hila Lulu Lin; The Discussion by Berest from 1983 (Julie M.Gallery – a deconstruction and analysis of an actual art discourse that took place in New York and discussed an inner-specific topic (narrative art) that the artist documented as an onlooker and elaborated into a series of works) and Curators’ Discourse by Galit Eilat and Max Friedmann from 1993 (Kalisher Gallery – a discussion held by curators on power centers in the local art scene and documented on video, an act that situated Eilat and Friedmann, as an interest group and as the initiators of the event and its recorders, in this power field itself) are only some additional instances, which may be referred to in this context.

The synchronization of those who are today using the medium of photography with the various mediums and cultural spheres derives from the influence of postmodernist theory (the ramifications of the “global village” are quite evident here – the young generation requires less mediation from schools in order to learn about what is happening in the world). As in the seventies, photography in Israel is once again integrated with art. The abolition of the hierarchies and the categorization of the various spheres points to a situation in which there is no one single occurrence, but infinite occurrences, i.e., there are no margins and no center. There are thousands of centers. Indirectly, the shattering of the institutional art center, which the artists of the seventies strove to bring about through their practices, is now a reality. The difficulty of defining today’s production stems from the fact that art has lost its comprehensiveness. It is nourished by, and conducts a dialogue with, a variety of intermingled spheres: computers, music, cinema, philosophy, science, politics, economics, etc. The dominance of technology in various spheres (computers, “virtual reality,” etc.) brings to the fore the problematics of simulation and fiction and the constitution of systems of meaning, and treads the same lane which photography opened in relation to the art discourse. The incessant transformations of technology reaffirm the status of photography in the conceptual environment in which it has taken abode. The visible applications, in uncompromising professionalism and finish, and the use of rich material (materials whose affinities to the media, to advertising and fashion recall the trend prevalent in the United States in the early eighties) master the concrete and subordinate the aesthetic to a discussion of values or, perhaps, to a material post-conceptual situation. | | | | Notes | | | 1. The most prominent of these is Dganit Berest. Other artists who, one way or another, have made use of the medium of photography are Arnon Ben-David, David Reeb, Pamela Levy, Yithak Livneh, Nurit David, (in works like Photography [1], 1991; Photography [2] ,1991 and in the text accompanying them).

2. In her article “ The State of Photography in Israel: A Stocktaking” [in Hebrew] (Yediot-Ahronot, Literature and Art supplement, 3 December 1982), Ronit Shany speaks about “a boomerang effect” operating on the photographers in their enthusiasm to become accepted by the Establishment.

3. Nurit David, The Photograph [1], in Nurit David Exhibition May 1991,Tel Aviv: Givon Art Gallery, 1991, p. 17.

4. Rosalind Krauss, “Notes on the Index, Seventies Art in America,” in October, the First Decade (see no. 29 above), pp. 11-12 (the essay was written in New York in 1976).

5. Craig Owens, “The Discourse of Others; Feminists and Postmodernism,” In Hal Foster (ed.), The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, Port Townshend, Washington, 1987, p. 59.

6 Gaby (Klasmer) and Sharon (Keren), for example, struggled with the problem of the representation of art which begins by rebelling against the art establishment only to end up in the museum as a material (i.e., as a form, as a language), found a unique solution to the problem: “display” with the aid of a rubber stamp.

7 To paraphrase the term coined by Joseph Kosuth, “conceptual stylist.” See: Joseph Kosuth, “The Artist as Anthropologist,” Gabriele Guercio (ed.), Art After Philosophy and After: Collected Writings 1966-1990, Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1991, p. 119.

8 Raffi Lavie drew my attention (in July 1994) to the fact that from a sociological perspective it is impossible to speak about Pop Art in Israel, because during those years the dominant mood was Zionistic, pioneering, and championed an ascetic lifestyle; the values of the affluent society did not yet exist here (even the only television channel did not begin broadcasting until the late sixties). In the catalogue of the Americanization of Israel’s Art exhibition (Bograshov Gallery and the Kibbutz Gallery, Tel Aviv, September 1989), Gideon Ofrat, the exhibition’s curator, made a similar claim, but also added: “…and nevertheless, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, intimate, oriental, sweating with Mediterranean sweat, scratching at a local recession, dressing up as an oppressive capitalist society and playing Marcuse games [...] quite arbitrarily adopted into this country forms and contents that originate in American protest and student rebellion against institutions, the administration, the army, the Vietnam war…”(Ibid., no page numbers). In a later article, Ofrat defined the conceptualism that emerged from Pop Art as a “distinctively Israeli hybrid, the fruit of a particular provincial retardation that mixes things that don’t go together.” (Gideon Ofrat, “Yoav Bar-El: The Image of the Concept” [in Hebrew], Studio no. 40, January 1993, p. 7).

9 During those years in Paris Aïm Lusky began constructing pinhole cameras with multiple apertures, which shatter the separate image and undermine the routine manner in which it is read/perceived.

10 Use of the formal photographic function of retouching (retouching is a conventional photographic technique for camouflaging and mending flaws). The crude retouching that Na’aman performs on the faces of the people does not erase a flaw, but creates one. The inversion of meanings serves an additional aspect of the strategy Na’aman employs in order to create a multiplicity of meanings (the Hebrew word for retouching, Ritush, has a double meaning, one of which is ripping and tearing to pieces associated with serial killers, for example), and to provoke discussion on subjects like wounding, murder, monstrosity.

11 From a talk I had with Haim Maor, July 1994.

12 The artists I’m discussing made use of photography mainly during the mid-seventies (some of them, still during their studies).

13 See. e.g., Raffi Lavie, “The Camera and Art” [in Hebrew], Pilpul Yotzrot, Journal of the Midrasha [College] for Art Teachers, September, 1982 For a long time now, photographers have complained about “Raffi Lavie’s negative attitude to photography,” and about the fact that because of his influence on what was acceptable to the Establishment, photography was always an “outsider.” It seems to me that had they really listened to him, they would have discovered that Lavie appreciated photography for its capacities, when these served a particular value, but did not worship it in itself. For him, photography is a tool like any other tool: ”…the camera is no less and no more than a tool. A tool with which one can make art and can also make non-art. As with any other tool.” ibid p. 38.

14 Many artists have mentioned to me the works of Bruce Nauman from the sixties and Vito Acconci from the seventies, and the influences of Ursula Meyer’s book Conceptual Art (New York, 1972), which arrived at the library of the Midrasha during those years.

15 Abigail Solomon-Godeau distinguishes between two kinds of photography – “photographic use in postmodernism,” and “art photography.” See her essay “Photography after Art Photography” in Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation, ed. Brian Wallis, New York: The Museum of Contemporary Art, in association with David R. Godine, Publisher, Boston 1984, p. 77.

16 From a talk I had with Michal Na’aman, June 1994.

17 A Turning Point, curator: Sara Breitberg-Semel, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1981; Here and Now, curators: Yigal Zalmona, Meira Perry-Lehman, Nissan N. Perez, Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, Fall, 1982. In relation to the latter exhibition, it is interesting to compare Yigal Zalmona’s essay on the postmodernist trend in painting with Nissan Perez’s modernistic analysis in his essay on photography.

18 In a talk I held with Michal Na’aman, she attributed this to photography’s becoming a tool of the center: “When photography stopped being a marginalized tool and became a tool of the center (a tool of mass production of the West), I lost my interest in dealing with it.” Yehudit Levin, on the other hand, spoke of the desire to abandon photography and to move onto painterly materials as a practice of camouflage, as an escape from the exposure that photography imposes.

19 Lisa Phillip’s, “Cindy Sherman’s Cindy Shermans,” in Cindy Sherman, New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1987, p. 13.

20 On the documentary work Jewish Gay Life in London, see: The Anglo-Israeli Photographic Awards, Jerusalem: Artists House Gallery, January 1994.

21 The most prominent of these is Dganit Berest. Other artists who, one way or another, have made use of the medium of photography are Arnon Ben-David, David Reeb, Pamela Levy, Yithak Livneh, Nurit David, (in works like Photography [1], 1991; Photography [2], 1991, and in the text accompanying them).

22 See note 1 above. Other influential artists who worked in Israel during this period and later studied in New York were Dganit Berest, Ronit Shany, Yigal Shem-Tov. On their return they brought a different spirit than that of their predecessors. Elia Onne, Eyal Onne and Yehoshua Glotman, on the contrary, who studied in England in the mid-/late seventies, brought back cultural values different from those of the artists who had studied in New York during the same period. While the New York group came back with values in the spirit of Arthur Freed, Phillip Perkis and others, and tended to deal with personal contents, the artists who came back from England are noteworthy for their involvement in the local culture and their concern with subjects of a social and political character. Other photographers who demonstrated a considerable presence during those years were Yosaif Cohain, who immigrated to Israel from the United States in 1971, and whose work inclined towards American photography in the spirit of Ansel Adams; Chanan Laskin, who in 1980 founded the photography department of Bezalel; Boaz Tal, who studied mathematics, film and television at Tel Aviv University and art at the Midrasha [College] for Art Teachers in Ramat Hasharon (1974-1978); and Judy Orgel Lester.

23 They also did not connect with Lee Friedlander, Dianne Arbus and Garry Winogrand, who in the sixties and seventies linked direct photography with values burrowed from the culture of Pop and mass media, and created an avant-garde alternative to the existing photography.

24 See note 15 above.

25 At the first International Triennale of Photography, which was held in Jerusalem in September 1973, for example, foreign photographers like Bruce Davidson (American), Eugene Smith (American), Donald McCullin (English) were exhibited, along with Israeli photographers such as Ron Havilio, Werner Braun, Richard Schwerin, Yoram Lehman, Micha Bar-Am, David Rubinger and others.

26 Glotman, Beyond the Frame (see n. 3 above), p. 3.

27 Ibid., Ibid.

28 At Bezalel, for instance, a photography department was founded in 1980; before this there was a photography unit within the Art department. At the Midrasha, in contrast, Garbuz began teaching photography in the mid-seventies, and from then on photography studies there developed gradually into the opening of a department that specialized mainly in photography, in 1984-1985. At any rate, at the Midrasha, photography studies were always a part of a broad study program, beside painting and sculpture. In the Midrasha framework, specific specialization begins only in the third year of studies.

29 See: Christopher Phillips, “The Judgment Seat of Photography,” in: Annette Michelson, Rosalind Krauss, Douglas Crimp, Joan Copjek (eds.), October, The First Decade, 1976-1986, Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1987, pp. 257-293.

30 E.g., The White Gallery, Tel Aviv (1978-1984) or the Gallery of Photographic Art, Tel Aviv (1982-1984).

31 In her article “ The State of Photography in Israel: A Stocktaking” [in Hebrew] (Yediot Ahronot, Literature and Art supplement, 3 December 1982), Ronit Shany speaks about “a boomerang effect” operating on the photographers in their enthusiasm to become accepted by the Establishment.

32 See Solomon-Godeau, p. 80.

33 Ibid., pp. 80-81.

34 In this context it is worth mentioning the activity of Ahad Ha’am 90 Gallery, which opened in April 1982. When Ami Steinitz became its director in 1983, he brought a pluralistic spirit and exhibited photographers who reflected this trend, such as Boaz Moshe, Yehoshua Glotman and Yanny Haaksman Klasmer.

35 Solomon-Godeau points to those qualities that made photography a privileged domain in American postmodernist art, but were rejected offhand by the art-photographers (see n. 15 above).

36 The Tel Aviv Galleries – Camera Obscura Gallery, which was founded in late 1983, Tatrama Gallery, which was founded in 1984 (and was active for about two years), Dimension [Meimad] Gallery, which was founded concurrently with Rega Gallery in 1986 (and was active until 1990), the Eugene Smith Gallery, which opened in 1986, and later became the Wrap Gallery (1987-1991), Artifact Gallery, which was founded in 1987.

37 In Europe, documentary photography has for many years been read through avant-garde rather than conservative codes. The prominent artists in this context are Bernhard and Hilla Becher, who began working in the sixties and whose work was classified then as conceptual, and their pupils Thomas Struth and Thomas Ruff, to mention a few names only. Local representatives who followed their example are Elia Onne in the eighties, and Gilad Ophir since the early nineties.

38 In her work, however, one can find an affinity to Western artists such as Jeff Wall. I.e., Barzilay deals with “here” and “there’ simultaneously, while most of the other young artists are more connected to the “global village” than to the local. The ramifications of this process find expression among other things in the local adoption of ideas and visual means from international artists (Ariane Littman-Cohen, Tamara Masel).

39 Natan refused to exhibit Milk, 1974, as an independent work (framed, hung on the wall) and thought the documentary framework had to be preserved.

40 Nurit David, The Photograph [1], in Nurit David Exhibition May 1991,Tel Aviv: Givon Art Gallery, 1991, p. 17.

41 Rosalind Krauss, “Notes on the Index, Seventies Art in America,” in October, the First Decade (see no. 29 above), pp. 11-12 (the essay was written in New York in 1976).

42 Craig Owens, “The Discourse of Others; Feminists and Postmodernism,” In Hal Foster (ed.), The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, Port Townshend, Washington, 1987, p. 5.

| | |

| | | |  | | Dganit Berest, Orlando, 1975, Courtesy of the artist | | |  | | Moti Mizrahi, Facing the Town, 1974 | | |  | | Moti Mizrachi, Leg and Wing | | |  | | Moti Mizrachi | | |  | | Eftat Natan, Flag, 1974, photographed action, Courtesy by the artist and Rosenfeld Gallery, documented by Tamar Getter | | |  | | Efrat Natan, Head Sculpture , Tel-Aviv, May 1973, Performance, Courtesy by the artist and Rosenfeld Gallery, documented by Yair Garbuz | | |  | | Yosaif Cohen, Our settlement, 1980s, Courtesy of the Photographer | | |  | | Pesi Girsch, Courtesy of the Photographer | | |  | | Pesi Girsch, Courtesy of the Photographer | | |  | | Roi Kuper, from the series Vanishing Zones, 1990–1994, Cortesy of the Photographer and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Nati Shamia Opher, Untitled, 1993, Courtesy of the artist | | |  | | Adi Nes & Naomi Talisman, from a documentary project Jewish Gay Life in London, 1993, Courtesy of the Photographers | | |

|